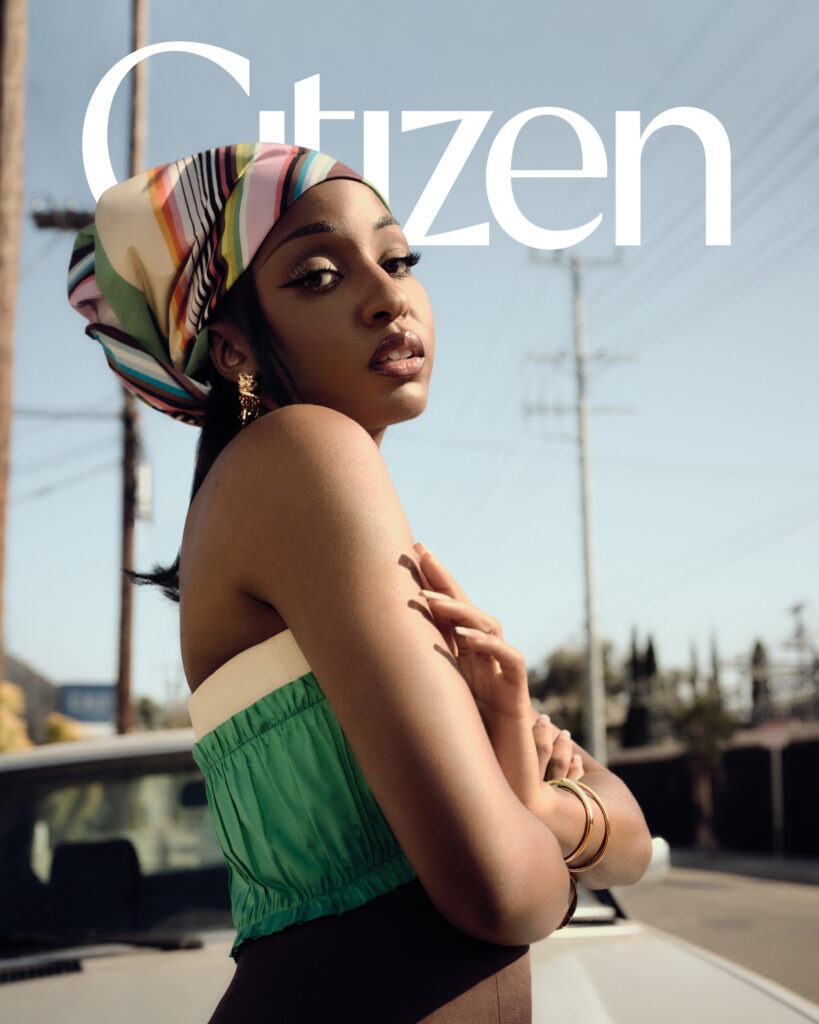

Ruth’s

A modern-day love story

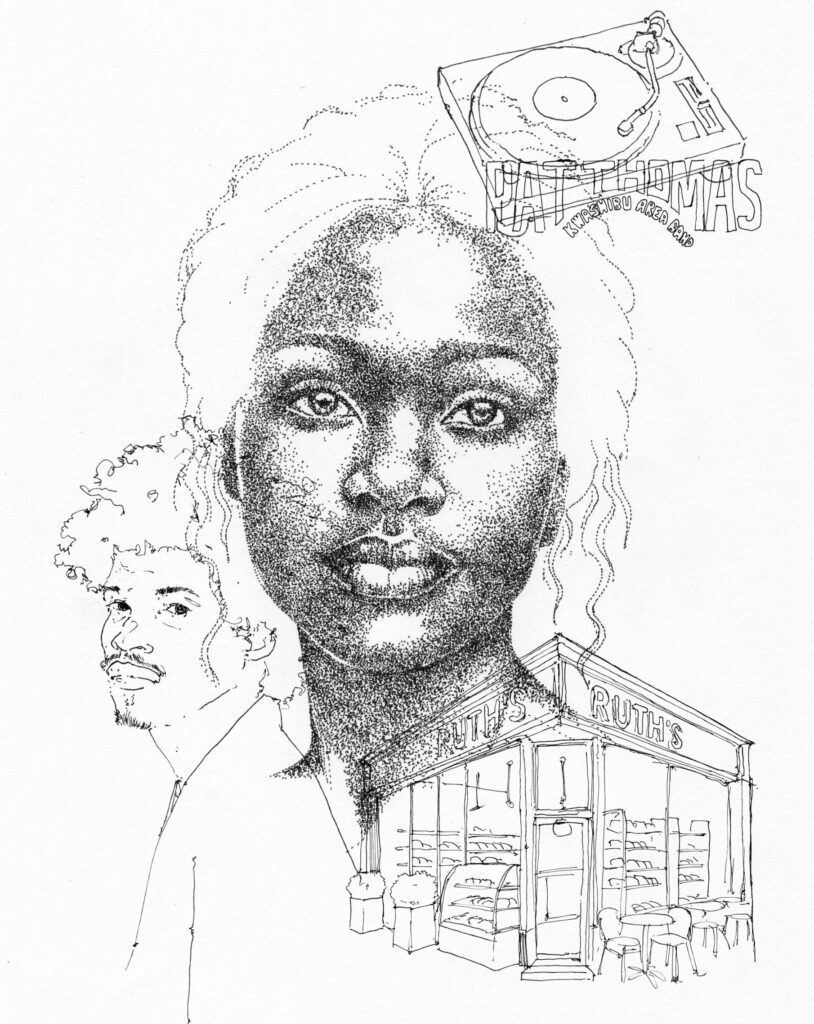

Text by Caleb Azumah Nelson

Illustration by Tejumola Butler Adenuga

Issue 004

These days are rarely void of surprise. Like how, despite living in London, each day we’ve been promised rain I’ve woken to a choking heat. Or, almost a year ago, when an ex, after a meal filled with comfort and laughter, suddenly blurted out that she wasn’t happy, hadn’t been happy, that it wasn’t anything particular but clearly this wasn’t working and, when she pressed me, I realised I wasn’t happy either, something didn’t quite feel right, which in hindsight was less a surprise and more an oversight, a lack of confrontation on my part. Or, recently, since the stroke which struck like lightning in his brain, how talkative my father has become, this man who was always the quiet storm in the corner of a room is now the light in any space he graces, the rumble of his laughter never far in a conversation. Maybe it’s because it’s just the two of us now, and grief which tore a hole in our lives has stitched us closer, or maybe it’s just that age has filled us both with more grace.

What’s unsurprising, as I come up the stairs of Holborn station, is a text coming through from Justin, cancelling. I’ve known him for decades and even now, in our early thirties, it’s always a bunch of excuses: missed train, or he’s locked himself out, again, or his recent favourite, since his doctor told him his iron was low: my anaemia is bothering me. I’ve long wondered why Justin has never trusted me with something I’ve heard him tell his girlfriend – I don’t feel like it today, I don’t quite feel like myself – but then I remind myself how much it actually takes to say those words.

The world goes on around me and as I stand, I feel the day falling apart in my hands. I start to walk, in no particular direction, no aim in mind, just knowing I need to feel like I’m moving or the day will run out of my grasp. I cut through one park, then another, emerging near Russell Square, ducking down a side street as the throng of kids on their summer holidays, aimlessly plotting, grows thicker. I walk a little further and that’s when I notice a hatch in a wall, where people are queueing for takeaway orders. A little further on, part of the same building, I see a larger door, like something you’d find guarding a barn, resting against the wall, gifting me a glimpse of an operating bakery. The sign above the door reads: Ruth’s. From inside, the smell of dough and sugar magicking itself into comfort and Sampha crooning from a speaker.

As I enter, a woman behind the counter glances my way. She holds my gaze but a moment, offering a tiny smile, before returning to her duties. I steal glances as she moves around, taking notes of the hair twisted in a plait round her head like a halo, the tiny tattoo of a swooping bird clinging to the back of her arm. The queue moves quickly and suddenly the woman is in front of me, waiting expectantly, a streak of flour running down her cheek.

‘You’ve got a little—’ I point to the side of her face.

She rubs at her cheek. Inspects the flour on her hand and shrugs. ‘Perks of the job. What can I get you?’

‘Erm…’ I scan the rows of pastries. ‘Everything looks good. Surprise me.’

For a moment, I think she might push back but then she nods and that tiny smile is back.

One of the other workers walks by as she considers what I’ll receive, saying, ‘I’m going on break, you’re on music duty.’ She nods and returns to scanning the baked goods.

‘What – erm – what kinda music you listen to?’ I ask.

‘What kinda question is that?’

‘What’s your name?’

She hesitates for a moment before saying, ‘Ruth.’

‘Is that a prerequisite to work here?’ She snorts.

‘Surely that did a little something for you in the interview?’

‘It helped.’

Behind me, the queue is growing. I watch her pick one pastry, then another. My time is running out.

‘Ok – favourite song?’

‘Favourite song?’ She looks offended. ‘Just one.’

‘Ok, top five. Come on, gimme something to work with here.’

The tiny smile broadens.

‘I’m gonna need some time for that.’

‘What time do you get off work?’ I ask.

She finishes packing the bag of pastries and hands them over. Taps at the till screen. Gestures at the card reader. I pay and she says, ‘Today’s not so good…’ She looks at me, waiting for me to fill the gap and I realise—

‘Nicholas. Or Nick.’

‘Nick. But tomorrow I’m done at 5pm.’ Our gazes meet and I nod. ‘Who’s next?’ The smile not leaving her face, nor mine, as I walk away.

Pops stays in an assisted living spot, a 20-minute walk away from my flat. I reroute back home, via his place, and find him as I do most days, tending to his orchids while something old and soft and tender – on this occasion, Marvin – plays from the record player. I watch him poking at the soil, checking the roots. He’s kept the plants for years but it’s only now, he says, he understands their plight: the difficulty of trying to stay alive.

He spots the bag of pastries I’m holding as I come into the open plan living room, and says, ‘And what has my favourite child brought me today?’

‘I’m your only child,’ I say, pulling out some of the pastries from the bag. I open one of the boxes to find a soft bun, parted in two by thick, light cream.

Pops is beside me, peering over at the box, unable to contain his anticipation. ‘Maritozzi.’

‘How’d you know that?’

‘Lorna, across the way, has been baking.’

‘That’s why you’ve got that smile on your face.’

‘Son, with all due respect, cut the chatter and serve the pastry.’ I hand him the box in my hand and open another to find a duplicate Maritozzi. We both pick them up with our hands, taking a bite. Our sounds of satisfaction join Marvin’s.’

‘This is good.’

‘From a bakery, near Bloomsbury.’

‘What were you doing round there?’

‘Meeting Justin.’

‘Surely, he cancelled.’

‘Absolutely.’

‘Ah well, his loss. Reminds me, are we still on for movie night tomorrow?’

‘Ah… we might have to reschedule.’

Pops takes another bite of his pastry. Studying me. Frowning. ‘You’ve got a date.’ When my silence confirms this, Pops claps his hands together. ‘Where’d you meet her?’

‘At the bakery. She made those.’

‘Oh, you’re in trouble. It’s about time anyway, you’re not getting any younger.’

‘I’m 34.’

‘You’re just proving my point.’

‘You’re 74.’

‘And you wouldn’t know it. You’re as young as you feel.’

‘And… you’re moving the goalposts again.’

‘I love you too, son.’

The next day, despite haggling over what to wear, brushing out the strands of my beard for the fourth time, I’m early to the park. Somehow, she’s earlier. Her scent is warm and sweet, like cocoa butter and sugar.

‘I made you something,’ she says, offering me a brown paper bag. I go to pull whatever it is out but stop short.

‘Where’s yours?’

She tries to mute a smile. ‘I already ate it.’

‘You couldn’t wait?’

‘I had to try it first!’

I shake my head, biting into the flaky pastry.

‘It’s delicious,’ I say, mouth full. ‘Wow. I didn’t even—’

‘You didn’t need to get me anything. The look on your face is enough.’

We walk on a little further. It’s a bright, long day – late afternoon feels like mid-morning – and everyone’s taking advantage of the glimpse of summer sunshine, dozing on picnic blankets, or tapping a ball between each other, or like us, doing that slow amble, beautiful in its meander.

We end up taking a seat on a bench. As we watch the city lounge in the heat, I feel the courage I had in the bakery desert me; I sense the courage it took for her to make something for a stranger desert her, too. There’s a nervous tint to her smile, her gaze wandering, finding her lap again and again, until I ask her, ‘How long have you worked at the bakery?’

‘I opened it a few years back.’

‘Wait. You played that down.’

‘I put my name on the door.’

‘Oh dear, oh dear.’ I shake my head as she laughs. ‘Please tell me I’m not the first to have done that.’

‘You’re the first person in a while.’

‘Same thing used to happen to my Mum.’ At her questioning gaze, ‘She used to run a bakery in Thornton Heath.’

‘Auntie G’s?’

‘You knew it?’

‘I’m Ghanaian, we all did.’

And I can’t help it. At her words, the grief, this old grief which is usually a spectre, barely a presence, gains form. Suddenly, I’m fourteen again, when my father was walking into my room, and I was confused because I had not seen the man cry, but back then, in front of me, he couldn’t stop, couldn’t get the words out. Here, now, I feel my shoulders turn inwards, my own gaze settling into my lap.

‘Alright,’ she says. I raise my head and turn to her. ‘Top five songs.’

She sees the smile she’s planted on my face and continues, raising a splayed palm, pointing to her pinky.

‘Five. Int’l Players Anthem.’

‘That is a very strong entry.’

‘Oh, I know.’ She sits back, satisfied.

‘What’s number four?’

‘Slow down, player. You’ll have to wait until I see you again.’

‘Ok. Well. What are you doing tomorrow night? I’m spinning records in Peckham.’

‘You’re a DJ?’

‘Yeah. You gonna come see me play or…’

‘Or…?‘I don’t think there’s an alternative. I think you should come.’

‘It’s a date,’ she says.

Whenever Pops spun records at home, he would describe himself as an architect, a man building homes out of sound with which to house our brief freedoms. Because, he would continue, a bottle of Guinness in hand, wiping the sweat of excitement from his brow, where else do you go where the gap between you and freedom is not a wide expanse but is so close you can embrace it? Where else do you go to step – literally step – out of your own way to make way for yourself? Where else do you go where something is wholly for you? Because the dance is for you, and only you. He’d shake his head as the words evaded him, as the language we speak failed him in this moment, his eyes ablaze, two tiny, joyous fires peering out, because that’s what it always felt like to me, like you’re on fire and you are the fire and rather than burning you are comfort, you are light, you are that place where you might lose control or you might not, but either way you’ll be ok. I always think about those years when I was a teenager, and it was my father and I, and it was hard, hard to watch my father do things he didn’t want to, to have to be at the whim of others, to watch him clamber slowly up the stairs and know something or someone, out there, had crushed his spirit. But then I remember those moments, when he would have a day off, he would drag his records towards the hifi system, and let himself become a fire in our living room. I remember, after the stroke, which I was so sure arrived after he’d worked a week straight with no days off, we both had, but he wasn’t young like I was, after the lightning had had its way in his mind and his left arm briefly abandoned him, all he wanted to do was let a bassline rumble against his body. And for the duration of a song, I could count on him moving, swaying. For the duration of a song, he was just my father, the flame.

This is what I’m always thinking about when I’m at the decks. When I’m playing, I guess what I’m trying to say, or ask, is when was the last time you weren’t encumbered by someone else’s desires? And if that moment wasn’t now, or now, or now, will you take one here? Will you let the fire overtake you? Will you become the fire?

I’m nearing the end of my set and because most of us in the room are from elsewhere, and we’re all trying to get back there, not just back to ourselves, but trying to get right, I play something from back home: Gyae Su by Pat Thomas. The room roars in response and I can’t help but grin. That’s when I see Ruth. I haven’t seen her for the whole set, but I do see her now. Her eyes closed, her limbs easy. A slight bend in her back, in reverence, in surrender. Her hand pressed to her chest. She stays like this for a moment, the other hands raised, before her eyes split open for a moment. She spots me seeing her and I see her seeing me. Even from the distance, the light in her eyes is clear.

By the time we reach Ruth’s, it’s almost four in the morning. I’m hot and sweaty and spent. Her flat is dim, yet even in the darkness, feels like I’m stepping into a warm invitation. She leads me through, past the living room, where I glimpse headphones, following the trailing wires to a set of decks.

‘You DJ, too?’

She shrugs. ‘Just for myself. And friends.’

In her kitchen, she pours me a glass of water. I drink, deeply, place the glass on the sideboard and lean against the counter. Ruth leans against the opposite.

‘You played number four at the end of your set.’

‘Gyae Su?’

‘It’s my Mum’s favourite,’ she says.

She takes a step closer, and another, and that’s when she kisses me, or I kiss her, I don’t remember. She tastes warm and sweet and before I know it, we’re pulling at each other, each tug gentle, each yearn soft. She starts to guide me elsewhere in the house when an alarm starts to go and won’t stop. We separate, breathless. For a moment, we can only look at each other, then she reaches for her phone. On the screen—

‘Time to bake.’ At my puzzled expression, ‘We get started early in the day, around this time. Even if I’m not working I wake up to bake.’

‘Well, don’t let me interrupt you.’

‘We’re not done.’

‘I’m not going anywhere.’ I can already see her eyeing her apron. With a smile, she reaches for it, sliding the loop of the strap over her head.

‘What do you want?’

‘Surprise me.’

She sets to work immediately. Taking the lid off a clingfilmed bowl, letting the dough roll out onto a floured worktop. Separating them into tiny balls on a silver tray, covering them with a tea towel. Another mixing bowl from the cupboard. Cream. Chocolate. Vanilla. Whipping. Beating. Deliberate in her music.

As she works, she taps at her phone screen and Al Green makes his ache known from a portable speaker. When we reach ‘Simply Beautiful’ on the album, Ruth holds up her hand. I count three fingers, and smile, realising what she’s saying.

All the while, I lean against the counter as I watch her fry off the tiny balls of dough, as I watch her conjure comfort with her own hand. When they’re done, she breaks one open slightly with her hands to let the steam out. Dips it into the chocolate mix. Raises her hand to my mouth. Her finger catches my lip as she feeds me the donut. The catch becomes a graze, a trace, and then our lips meet again, and then Al Green’s ache becomes ours, or rather, our aches become one and the same. We pull away from each other, smiling. Outside, the birds have already begun their song but night still swallows day, the sky a purple flame. I kiss Ruth again, and the night swallows us, too.

Summer stutters its way into autumn. Time somehow stretches and flattens; a week with Ruth becomes a month, a month becomes three. Because it’s summer, the demands on us increase. I’m gigging more heavily as people clutch onto the last of the sunshine months. Ruth accompanies me when she can, but usually, by the time I’m finished, she’s due at the bakery. When I go to pick her up from work, or glimpse her in action, the tiredness has made a home on her face. I think that’s why, one evening, sprawled on my sofa, I say to her, ‘We need a holiday.’

‘Funny you should say that,’ she says.

‘Go on.’

‘I’ve been asked to work at someone’s corporate retreat. Run some baking sessions. Make a few bits. Somewhere in Spain, next week, for a week. I’d only be working half the time. And I was thinking…we could go together?’

‘You don’t have to ask me twice.’

‘Only thing is – my Mum’s coming into town. Right in the middle of the trip. I haven’t seen her in years. She hasn’t seen the bakery.’

‘Ok.’ I consider. ‘So what do you want to do?’

‘I want to go to the middle of nowhere with you, come back and have you meet my Mum.’

I smile. ‘We should do what we did with my Pops.’

A few weeks before, I’d grown tired of my father asking, ‘When am I gonna meet your little girlfriend?’ On one of my weekly visits, I went not just with baked goods in tow, but with the baker herself. My father opened the door and was immediately flustered – ‘If you’d told me we were having company I would’ve had a haircut.’ – but welcomed us in as if we were both his children, playing us some of his deep cuts while he described in detail just how good each of Ruth’s pastries was. He worked himself into such an excited frenzy that he quickly fell asleep after dinner, they both did, curled on the sofa, content.

Ruth laughs at the memory. ‘Maybe not. Mum scares easily. But you will meet her.’

‘Like I said, you don’t have to ask me twice.’

The week away takes on a steady continuous rhythm, a loop which deepens with each pass. Waking early to the sound of the ocean crashing because we’re so close. A morning walk across the sand, hand-in-hand. Watching from a distance as Ruth carefully, tenderly instructs on how to make flour into something warm, light, fluffy but always beautiful, or in my own space, headphones on, surrounded by sound, working on how I can build more homes for freedom with music. But always coming together for a phone call with my father which always ends with God bless the work of your hands. The languor of our time. Night arriving like the day was never there, a glittering sheet of stars up ahead. Chasing a mosquito out of the room while she laughs at my efforts. Lying across from each other, breathless, panting, in the wake of our closeness. The tap of her fingers on the screen. The phone on the pillow between us. The v shape of her fingers I realise is the number two. Peace of Mind. Lauryn Hill sings of desire and this moment feels so sure, so pure.

A week later, we’re back in Ruth’s kitchen. She’s at the counter, giving some dough the work. I sit on a stool, gazing at her. The light in her eyes glows dull and her brow is furrowed.

‘Do you need any help?’

She gives me a short, sharp shake of her head, and carries on kneading dough, little plumes of flour rising up with each push of her fist. Outside, the sky rumbles and water pelts the ground and the heat chokes the air.

‘I can feel you watching me,’ she says. ‘I’m ok.’

Her Mum didn’t get on the flight she was meant to, delaying it so she would arrive when Ruth arrived back in London. There were four days until her new flight. Days one and two proceeded as normal but on the third day, she told her sister, I don’t feel like it today, I don’t quite feel like myself, complaining of a pain in her arm. The pain migrated upwards, downwards, until her whole left side felt like a hot flame. The stroke thundered about her skull and she quickly lost consciousness. Now, I’m watching Ruth thundering about the kitchen, a brewing storm. She has a flight in the morning, back home, to be with her Mum, but I knew there was no use in trying to convince her to sleep. I watched her over-whip a ganache into a stiff cloud and now she’s in danger of beating this dough past the point of submission.

I stand from where I sit, placing myself behind her. I place my hands on hers and the vigour with which she’s attacked the dough begins to slow. I rest her heart against mine, leaning into her, encouraging her to do the same.

‘I’m just so angry at myself. If only she’d come when she was supposed to, if I’d been there.’

‘You weren’t supposed to know,’ I say.

‘I know, I know.’ She takes a few deep breaths. ‘I just don’t know what I’m supposed to do with all this anger.’

A few hours later, I’m driving her to the airport, the only sound in the car air whooshing through a gap in the window. I flick on the radio. Where we are must be a dead zone, there’s only static. When we reach the traffic lights, I open my phone. Play Lauryn Hill’s ‘I Gotta Find Peace of Mind.’ Her smile is so sad as her head leans against the window, letting the sound wash over her. She begins to sing quietly, the music coaxing her out of herself. Not away from her anger but towards it. Not into submission but into surrender, that place where you might lose control or you might not, but either way, you know, eventually, you’ll be ok.

When we reach the airport, unusually, everything is seamless. We then stand by the entrance to security, this point of separation, not realising it would arrive so soon.

‘I don’t know when I’ll be back,’ she says.

‘I’ll be here.’

She throws her arms around me. That familiar scent of cocoa butter and sugar. She doesn’t let go. Neither do I. I feel her shudder in my arms. The shudder becomes a shake. Her cheek is wet against mine. I hold her closer because I know what it’s like to grieve someone who hasn’t passed. I know what it’s like to feel the fire and not know if you can step into the flame in case it consumes you. I hold her for as long as she needs, as time stretches and flattens where we Stand. When we separate, I say, ‘You got a little…’ pointing to her cheek. She laughs and I wipe at her face with my thumb. She clutches the handle of her carry-on and goes to turn away—

‘Wait. What’s number one?’

Ruth raises her eyebrows.

‘Your favourite songs. What’s number one?’

Her smile starts small, like the first she gave me, then broadens. She takes a step towards me, pulling me closer. Her lips to my ear, she says, ‘Ours.’ And then, with a squeeze, she turns away, heading onwards, through the security gates. But not before she gives me one final wave, letting me see the light in her eyes, like two little fires, one last time.

‘Nick. But tomorrow I’m done at 5pm.’ Our gazes meet and I nod. ‘Who’s next?’ The smile not leaving her face, nor mine, as I walk away.