Wardell’s Day

Wardell’s Day

Jelani Cobb remembers the contours of childhood disappointment and contemplates the seeming randomness which determines how a life turns out

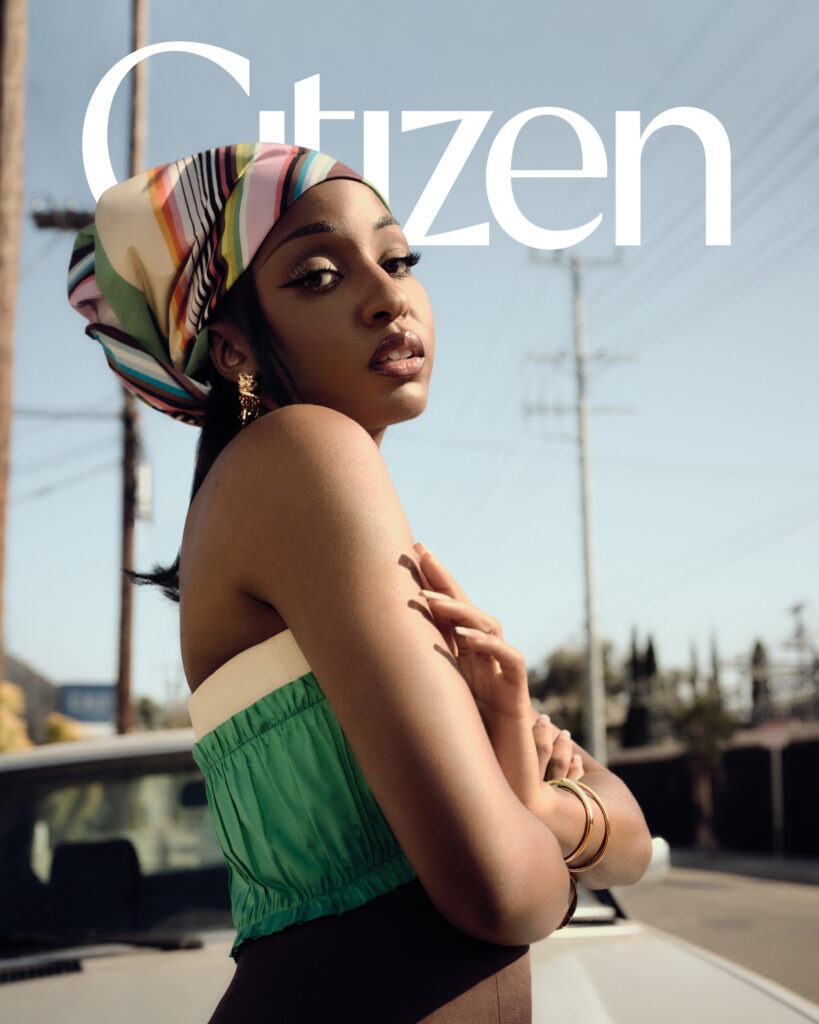

Text by Jelani Cobb

Photography by Dawoud Bey

Issue 001

The request came from his mother to my mother. Wardell Day, a kid who lived four houses down and across the street would be starting school in the fall and would I be willing to walk him the four blocks down Hollis Avenue to PS 134 each morning. I must’ve been eight, no more than nine. It was 1978 and eight, maybe nine year olds were not then consulted about their prior commitments before being signed up for new ones. So,it was decided between two mothers that,when classes resumed I would meet Wardell at his front door and walk up 200th Street to Hollis, we would then turn right, walk down to 204th street, and cross the avenue which would bring us to PS 134. He would go to the kindergarten in the main building while I went on to the temporary annex that housed the fourth grade. I didn’t know much about him. He was about to turn five and I was old enough to cross the street by myself, which seemed to be nearly as wide a gulf as the one that separated childhood from the world of the grownups. He was half my size, light-skinned and immediately took to following me around the neighborhood.

What I knew of the Day family was spotty.

Wardell’s mother was named Diane.

She smoked Newports and wore her hair in stiff finger waves.

She had deep brown skin, spoke with a raspy voice and during warm weather would sit on the front steps listening to WBLS on the radio.

To my mind she seemed much older but she was about twenty-two at the time, roughly my older sister’s age. They would get together sometimes, smoke cigarettes and talk about men, their kids — my niece was two years old — and whether the upcoming music festivals seemed worth attending. Their rapport was forged through the mutual knowledge of the unreliability of men and how it felt to return home single, with a small child, trying to figure out what came next. Diane’s mother, an older woman who, like most of the women her age on that block, had come up to Queens from somewhere down South. Diane had a sister, whose real name I don’t recall because she was known as Sister both within and outside the family. Sister lived there as well, a part of the matriarchy that surrounded Wardell, a cocoon doting over him, scrupulously monitoring his manners and poring over his clothes to ensure that he left the house spotless no matter what levels of filth he’d acquired by the time he got back home. And, here they were entrusting me with his safe passage to and from school each day.

It was hard to see him as anything more than a responsibility I had not asked for. Each morning, he waited then followed me a beaming four-year-old acolyte, devout and adherent. And when he learned that our birthdays were just twelve days apart–his on August 9thhe held onto that fact in his tiny mind as the thing that cemented our fraternal bond.

We navigated our way to school that year, mostly without incident. One cold morning, though, as we stood on Hollis Avenue waiting to cross, I noticed a packet of mustard on the sidewalk and stomped on it. A yellow-brown jet shot out of the plastic pouch and landed on Wardell’s sweatshirt. He began to cry, worried that his grandmother would be angry. Fearing the same, I tried to wipe away the mustard smearing the stain further across his chest. I convinced him to continue on to school rather than returning home, which proved to be a mistake. When we got back that afternoon his grandmother looked at his shirt, pursed her lips and asked what happened. We told her and she looked directly at me and said “You should have come back home. We do not go to school this way.” I only grasped what she told me as a rule — another of the byzantine and seemingly infinite number of laws that adults seemed to have committed to memory but children could only guess at. The principle seemed amazing in its specificity: If you happen to stomp on a packet of mustard and that mustard sprays all over someone’s shirt you must return home immediately. What I understood later was that she, like other black Southerners, took particular concern about outward appearance as a measure of not only cleanliness but how seriously one took their commitments to family. Slip up and you would be mistaken for the type of people my father called “common.” My father had grown up in Hazlehurst, Georgia, scraping through the Great Depression in a place where poverty was nearly a given for black people. But even then, there were tiers: there were those who went to church, kept whatever conflicts they had inside the house and, who, despite owning barely more than a change of clothes, scrubbed them in a basin as if they were also scrubbing away the stigmas imposed upon the race. Then there were those who were “common”. The Day family, she was telling me gently but firmly, was not common.

Nor was Hollis, and this was deliberate. Like most of Queens the area had been predominantly white in the fifties. But twenty years later, it had become home to a burgeoning black middle class of civil servants and union workers, their status attested to by the stream of children who headed out the door each morning in the yellow shirts, blue slacks and blue plaid ties of St. Pascals, the Catholic School on 198th Street. The rows of neat, symmetrical lawns — squares that seemed like the answer to a question about the precise minimum amount of grass required to qualify as middle class — spoke to a sense of possibility for people who were not affluent but were just successful enough to be self-conscious about it. My family had come to Hollis in 1967, graduating from a series of walk-up apartments in Harlem and the Bronx to home ownership in the outer boroughs. When I was born two years later it was possible to see Hollis, and the wide, tree-lined aisle of 200th Street in particular, as a metaphor for progress. The yield of the hundreds of black people who’d gotten themselves clubbed and water-hosed in hopes of securing a new day. I started school at St. Pascal’s but by the third grade the costs of private education for me and my older brother and sister had grown too high and my parents, with what seemed at the time like exaggerated seriousness, broke it to me that I would be transferring to the public school the following year. The symbolic distinction between a school with “Saint” at the beginning and one with “P.S.,” the New York City designation for a public school, was lost on me at the time. But it was not lost on my parents.

“It was hard to see him as anything more than a responsibility I had not asked for.”

One side-effect of our somewhat less middle class status was the fact that I was now available to walk Wardell to school each morning. Over the course of those walks I gradually warmed up to him. And, he looked up to me just enough that I could easily talk him into being an accomplice in my childhood misdeeds. When his grandmother turned over the soil in her backyard to plant a garden we seized upon the chunks of earth and put them to use as dirt grenades in our war games, delighting as the fist-sized masses of soil detonated when we hurled them against the back fence. No amount of his grandmother’s chastisement could curb that habit but we did quit abruptly when she hired a man to offload a pile of cow manure to fertilize the patch. During another incendiary stretch I talked him into being a lookout while I made “campfires” on the curb out of piles of twigs, leaves and, inscrutably, deflated balloons. That one ended the first time we were caught by his seemingly omniscient grandmother. Then the summer arrived and with it came Wardell’s father, Raymond.

He moved into the house on 200th street with Wardell, Diane, her mother and her sister who was also known as Sister to everyone else. By that point I had come to understand family as an assemblage of people thrown together by fate, obligation and chance but not necessarily by blood so I don’t think I had ever questioned where his father was or why he didn’t live with the family. But when he showed up one day, I could sense how much things had changed. The question:where he had been all this time, didn’t occur to me but his presence created a new center of gravity in the household. Wardell, who I realized looked like a smaller replica of Raymond, and who I didn’t remember ever mentioning him before, began to talk incessantly about his father. Diane was equally enamored of him. It was easy to understand why.

Raymond wasn’t tall but he was muscular and light-skinned in an era when that was still considered a virtue. He had style and favored hood chic combos of sneakers, jeans and sunglasses. He was the first person I knew who could be described as charming. The solemn edge to his personality was paired with an incandescent smile that would put people at ease but only on his terms. I was big for my age, big boy, big feet. hen my frustrated older sister would tell me to “act my age, not my shoe size,” I’d dimly reply that those were the same thing.

One day when I was standing outside waiting for Wardell he gave me the once-over and asked what size shoe I wore. I replied that I was a size ten. He disappeared into the house and returned a few minutes later with two shoe boxes. Inside were the newest Pumas, a green pair and a blue pair, the brilliant white soles still unscuffed. Then, Pumas were the thing, years before RunDMC rapped about Adidas and people started offloading them like a broker trying to dump a bad stock. I ran back home to put on one pair, ignoring my older brother’s advice to wear one blue sneaker and one green one in order to signal that I had two pair of Pumas in my closet. Wardell had told me about his father’s superheroic qualities and looking into the mirror withnew kicks still gleaming on my feet, I was convinced of the gospel, convinced my young friend had spoken the truth. The day Raymond left, was in the fall.

It was the afternoon and I was in the front yard with my older sister. It was still warm enough that people along 200th Street were out walking around or doing yard work. A car screeched around the corner on the south end of the street and barreled toward Hollis Avenue. Then, in the middle of the block, it swerved to the right and skidded onto Wardell’s lawn. Raymond jumped out and ran into the house. Minutes later police cars came barreling down 200th street from both directions, until a small army of cruisers was parked in front of Wardell’s house lighting up his home in a pulse of red and blue light. My mother sent me inside. I climbed into the window and watched as police blocked off the street and more people came out of their houses to see what was going on. People began to gather around the yellow police tape that seemed like an insult to what we knew or thought we knew of our neighborhood,people who’d left Harlem to get away from car chases and police cordons, people whose parents had left small homes with dirty yards in the South, and all such other things that meant that you were common.

By nightfall the situation had become a standoff. My sister and brother drifted down to the police line. She came back and I overheard her tell a friend “He robbed a bank.” A cop with a bullhorn told Raymond to turn himself in. I remember the sound of Diane’s voice, yelling down from a bedroom window “He went out the back door!” He hadn’t. They knew it. Police surrounded the house and were posted in the backyard, tromping around the same garden that Wardell and I had raided for our arsenals of dirt. I recall being bewildered that she would tell such an absurd lie but years later it seemed to me that one potential definition of love, or possibly of desperation, if there is a distinction between those two things, is the willingness to yell unbelievable lies on your behalf to a squadron of cops who are, at that moment, threatening to kick your fucking door down. If Raymond was going to jail or the morgue, he’d depart certain of his woman’s love and allegiance. He wound up in the former and the morgue went hungry that night. Raymond came downstairs not long after Diane yelled out the window. The cops cuffed both of them, put them in squad cars and drove off. They towed the getaway car out of the yard but the skidmarks on the precious lawn were still there the next morning along with bricks the car had knocked out of the front steps when it came to a stop.

“And when he learned that our birthdays were just twelve days apart — his on August 9th—he held onto that fact in his tiny mind as the thing that cemented our fraternal bond.”

I didn’t walk Wardell to school for a while after that. And when we did see each other again our relationship was different in ways that even a ten year-old and a six-year-old could perceive. We had surrendered some portion of childhood to the knowledge of what shame looked and felt like. I still wore my Pumas but they were no longer fresh and I figured out they were probably stolen when I got them. Raymond had gone to prison shortly after Wardell was born and his time on 200th Street had been a brief intermission between that bid and the one he did for the bank robbery. The cocoon of female attention that surrounded Wardell in that house had been an expression of familial love but also an attempt to counter the absence of his father and the burden of his eventual knowledge of where his father had been all those years.

Diane came home a few days after the fiasco but I never saw Raymond again. One day a few weeks later as I stood outside bickering with Wardell about some meaningless concern an older kid named Stanley, the neighborhood lout, breezed by and mumbled under his breath “Tell him at least my dad is not a jail bird.” I froze, horrified. Wardell ran into the house in tears. When Diane came down to confront me about it I tried to explain that I had been stunned by Stanley’s cruelty. I loathed Stanley but the words to defend my friend had escaped me. The tendril of connection that still binded us seemed to sever after that. The breach never had time to heal. Not long after, I had my own brush with commonness and we moved away from 200th Street.

On Christmas Eve, 1979 we received word that my oldest half-brother, a Vietnam veteran who’d come home addicted to heroin had died of pneumonia. It was years before we made the connection that he was likely an early victim of AIDS. My father began drinking heavily after that and in a short succession the house fell into disrepair and then foreclosure, but not before the indignity of falling behind on the water bill and having the entire neighborhood see us take water from the hydrant in front of the house to meet our daily needs. Our failures were a kind of betrayal of what that Hollis was supposed to be. I took to walking to school alone and avoiding all unnecessary social contact. The tradeoff for shame is, if you allow it, a heightened sense of empathy, but I don’t think either Wardell or I wanted to learn how to empathize so acutely. Or at least not in the way we did.

The next time I saw Wardell I was twenty years old and riding the Q4 bus down Farmers Boulevard. I was home on break from my second year at Howard University and going to visit a girl I was dating who lived in St. Albans. Wardell got on not long after I did, his face alight with a trace of his childhood exuberance when he recognized me. He’d grown into a mirror-image of Raymond, handsome, with a hint of his charm but none of his guile. His family had moved back down South, he told me and like me he was visiting New York over the summer. We joked about our old neighborhood until I reached my stop. We promised to keep in touch but didn’t.

Hollis stays with me in ways that I don’t entirely understand. I awoke at 4 a.m. one morning and for seemingly no reason I could discern took a taxi from Manhattan, where I now live, thirteen miles to the third house on the right on 200th Street, just off Hollis Avenue. Later it occurred to me that I wanted to see if the fire hydrant looks the way it did in my dreams. I walked over to PS 134 and saw that the building looks exactly as I remember it, except that it is now named after Langston Hughes, and the temporary annex is still there forty years later. My father once told me that there is nothing so permanent as a temporary solution. The block the school sits on is now named RunDMC and Jam Master Jay Way, after Hollis’s most famous sons. I know no one there anymore, but I’ve returned to the place about once each decade, an erratic salmon working his way against the currents.

The last time I was there I was jolted by the memory of when I was twenty-eight and nearly died of a toothache. I’d gone to a wedding in Washington, DC when my tooth began bothering me. I made an appointment for the following week and tried to focus on my friends’ impending nuptials but by the time I returned home I was feverish and verging upon delirium. I was living in the Bronx and went to Jacoby, the public hospital near me where a doctor told me that the tooth had become infected and was threatening to close off my airway and asphyxiate me. I had surgery that same night. In the haze of recovery my mother visited me and we talked about the old times in Queens. Then her tone shifted. She’d run into Diane not long before she came to see me. “Wardell is dead,” she told me.

He’d come to New York over the holidays and visited a video arcade. A dispute broke out with some other people there and one of them pulled out a gun and shot him point blank. He was twenty-four. His age seemed to roll around in my head like a pinball. I’d met him exactly twenty years earlier when he was half my age but had already lived one-sixth of his short life. I lay in the hospital bed numb, pinging between relief that I had dodged mortality and grief that he had not. That was twenty-three years ago and still his memory abides me like a ghost limb, his wide, missing-tooth smile as present and indelible as my own daughter’s.

At forty-eight I realized that I’d become twice his age again. That was three years ago. I still ponder the capricious cruelty that first took his innocence and then took him in his entirety, the indifferent script that spared me but not him, and how he was the first responsibility I was ever charged with. Part of me feels responsible for him even still. I think of Wardell regularly but most predictably on two occasions: on August 9th when I quietly acknowledge that he would be four years younger than whatever age I turn twelve days later. And again, when the autumn leaves turn orange and I see children flush with excitement, wending their way to school, the older ones shepherding the younger ones, a hand wrapped protectively around a hand.