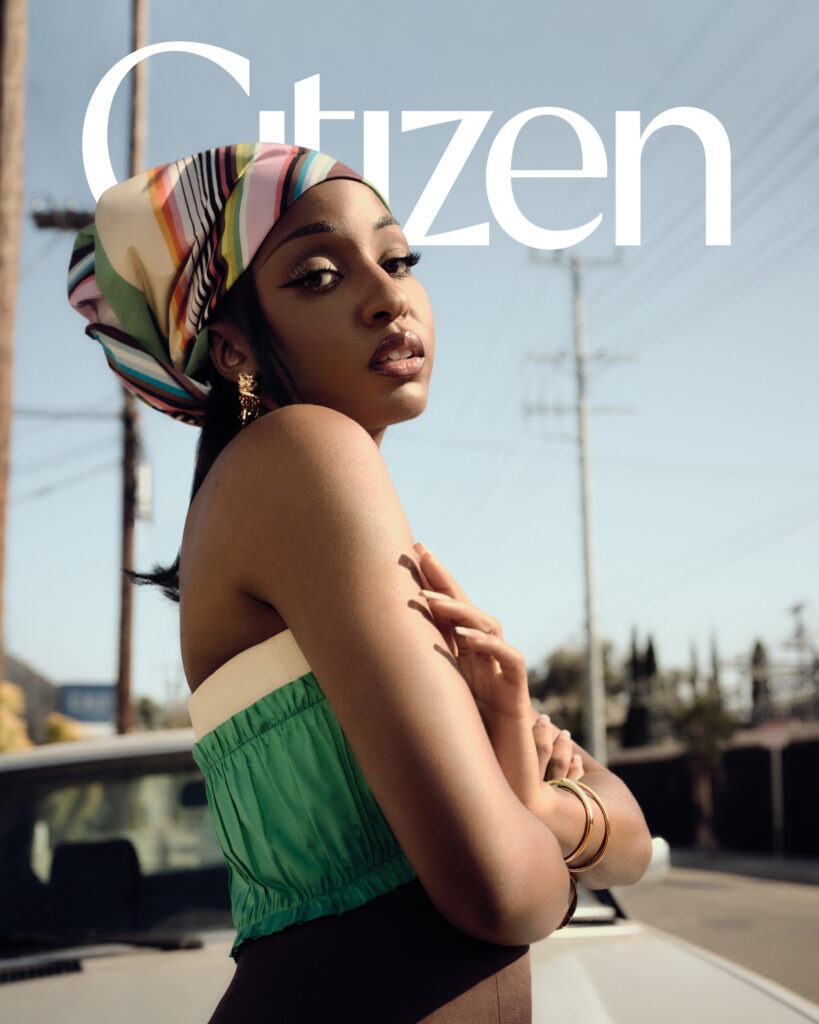

The Last Great Party

The Last Great Party

In pictures and words, Honey Dijon shares the contours of her changing world and the city that shifted with her

Text by Honey Dijon as told to Citizen

Issue 001

There is a consistent commentary, this enduring view, that New York City was once great, that the city has lost its edge, its heart, and its grit as places and spaces of refuge, where one need not be very rich to be very much a part of all the things that made the city move, all the best parts. But what becomes of a city that is stripped down to its joints and laid bare before a long and enduring calamity? Can it transform itself into something new, or even into something old? Can the city take its cues from a person who has done the same—disassembled what she had become to be what she should be? Citizen sat down with Chicago-born DJ, Honey Dijon, and her collection of photographs to take a look at what she describes as New York’s last great decade, and a time in her own history when the city and woman were one and the same—full of new possibilities.

“You couldn’t live in the day world. There was no space for you.”

“Back then…The clubs were a community for marginalized people, where they could be trans or an artist or whatever didn’t fit into the box.”

HONEY: When I moved to New York in the late 90s, I was at a turning point in my life. I was born in Chicago when house music culture was just beginning, and I literally structured my life around going clubbing. In the late 1990s, I was working at the Meridian Hotel as an overnight telephone operator. I got fired from that job because I was always late.

I didn’t move directly from Chicago to New York; instead, at the time, I had this friend who worked in Washington, D.C. who said that they could get me a job there. And, because I felt like there was nothing else for me to try and do in Chicago, I moved to D.C.

When I was still in Chicago, I had met a deejay named Gant Johnson who was very pivotal in introducing me to the New York scene. And, before I left Chicago, he told me, “If you’re in New York, look me up.” So, when I moved to D.C., I took him up on that offer.

I started going to New York on the weekends. Being in New York was like a revelation. Gant was involved with the Lower East Side community of drag artists and musicians. And, at that point, I still wasn’t aware of my gender. But, New York was super vibrant, and I found my community there.

Then, I got fired from my job in D.C..

I could not keep a job! Fortunately for me, the company I was working for was folding the division I worked in, so I got $3000 in severance pay. Back then that was a lot of money. So, I took all my belongings, put them in storage, and moved to New York. For the first three months, I slept on Gant’s floor while I searched for an apartment. The apartment I eventually found, I still have to this day. (After publication, Honey moved from her NYC apartment).

Like many trans women, I started out as a drag performer, and that’s sort of how I made my name in New York. It was an honest way to make a living, and I think it was also a safe place in your community [for someone who was transitioning] to become who they were, especially in the early stages when you are quite visibly transitioning. At that time, it was either sex work, performing in a club, drug dealing, or a combination of all three. You couldn’t live in the day world. There was no space for you.

One night, my friend Gant Johnson and I were watching TV when a commercial for Honey Dijon came on. The voice from the TV said, “It’s spicy and sweet,” and Gant was like, “That’s you.” At the time, I needed a name as a performer, so we put it on a flyer, and it was done. I was Honey Dijon.

As I performed, I started to meet other trans women and they were like, “Oh, we see you; you should be known.” They saw me before I could see myself. Ultimately, it was a continual coming out because first, if you’re born in a male body and you’re super effeminate, you’re shamed for being a sissy. Then you sort of start to question your gender, and then you’re shamed for that, too. So, I’m grateful to have had those women who could be there to see a way for me when I could not quite see it yet.

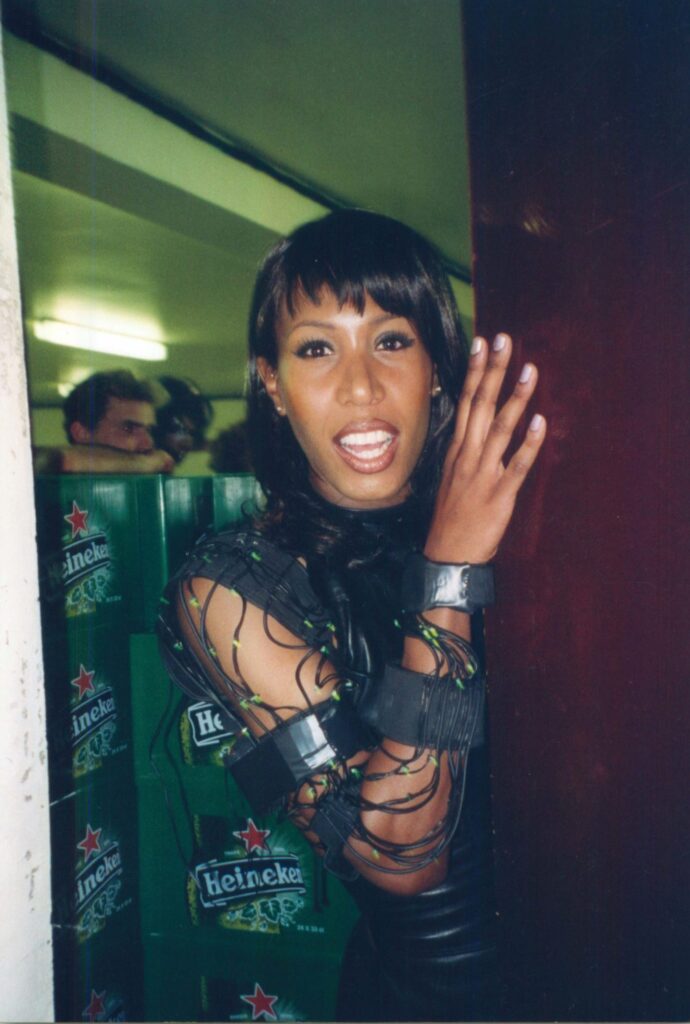

I transitioned at the same time that I started a deejay career, so both were done very publicly. But I started deejaying out of necessity. I had been in New York for a few years and made a name for myself as a performer. I had a lot of access to promoters and parties and clubs and things like that. A friend of mine named Ted Patterson came to me one night and said, “You have really great taste in music. You’d be really good if you learned how to deejay.” So Ted took me under his wing and taught me the mechanics of deejaying.

Around that time, I transitioned out of doing drag because at a certain point, I realized I never identified as a boy. There’s this crossroads with a lot of trans people when you’re performing—you have to decide if you are going to be the caricature or are you really going to make that into the person. Is this dress up, or is this who you are? I decided that this was who I was as a person.

During that time, in the back of my mind, I always knew that if I really needed to go home, I could. I also knew that I had to let my family come to terms with my decision and who I had discovered myself to be. But I always knew, like, if I didn’t have any money or if I was homeless, I could always go home. So that gave me a lot of courage.

From 2002 to 2005, I was in my early transition from becoming who I am, discovering what type of artist I wanted to become, and discovering New York itself. Back then, nightclubs weren’t just places of entertainment. The clubs were a community for marginalized people, where they could be trans or an artist or whatever didn’t fit into the box. The New York club scene was a place to make a living, to find yourself, to find other people, to find partners, a place to develop yourself. I mourn the gentrification that has happened to New York City for a reason that many people don’t talk about—the gentrification and the metamorphosis of downtown or even some parts of Brooklyn has wiped out the places where you could experiment with self and find acceptance.

When I first started deejaying, it was to pay the bills, deejaying at a restaurant bar. I’d deejay if there was an opening of a matchbox; then I could make some money. I would do it because I deejay weddings. I just did the work to get what I wanted, which was the surgeries to help me present the way that I present my version of womanhood. I didn’t do this thinking, “I’m going to be famous.” I was making 150 fucking dollars a night, four to five nights a week. The fuck are you going to get rich from that? You know, I just want to be able to make a living to support myself. And, I just did the work to get what I wanted, which was the surgery to help me present the way that I present my version of womanhood.

A lot of my early deejaying work was through friends, and I was transitioning at the time, so the gay clubs were still a place where I could feel safe and find myself. Sometimes, I gave a combo meal, sometimes you got a show and a deejay. It was never an agenda. I had been doing all of these gay bars. And one bar in particular that was really popular at the time was called the Cock, it was on Avenue A and 12th. Everybody came to the restaurants like everyone from Narciso Rodriguez to all the other world-renowned fashion designers. That’s how I got into fashion.

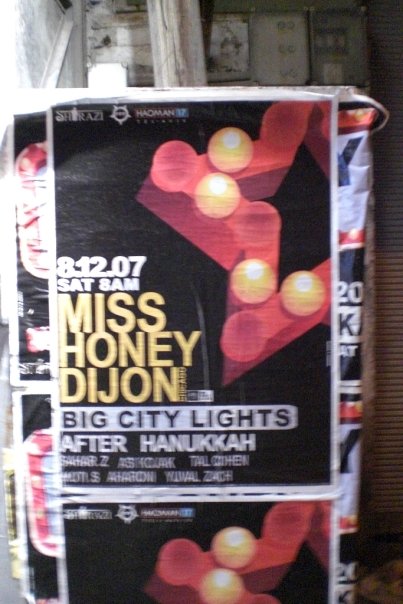

But, the thing that really made me as a as an artist, was a party called Hero. It was at the Maritime Hotel on the 16th. I became a resident there in 2007, and it was probably the last big New York party that was a child of the sound factory. It ended in 2010, I’ll never forget it, because from 200–I think I started in April of 2007. Every Sunday we would get about twelve hundred people. On holidays we would get up to two thousand people and it was amazing! I still have the picture of me with Alexander McQueen. Riccardo [Tisci] invited me to deejay parties. It’s where I met Ken Jones in 2003. So many of the relationships I have, the relationships that built me up professionally were born out of clubbing and music.

Hero really gave me my profile in New York City and an international profile until the stock market crash of 2008. Everyone was living on credit then, people were coming to the club and, baby, they were like, a round of drinks to everybody, credit card, credit card, credit card. A lot of people lost a lot of things. People weren’t shopping anymore and the crowd we brought in year Sunday went down from twelve hundred people every to about 500, 600. So the party ended, and that’s when I started coming to Berlin,.

New York has changed. You know. But I’m grateful to the city for what it was during those years, I was in my early transition from becoming who I am and discovering what type of artist I wanted to be, all while discovering the community of New York.

Images courtesy of Honey Dijon