The Center

The Center

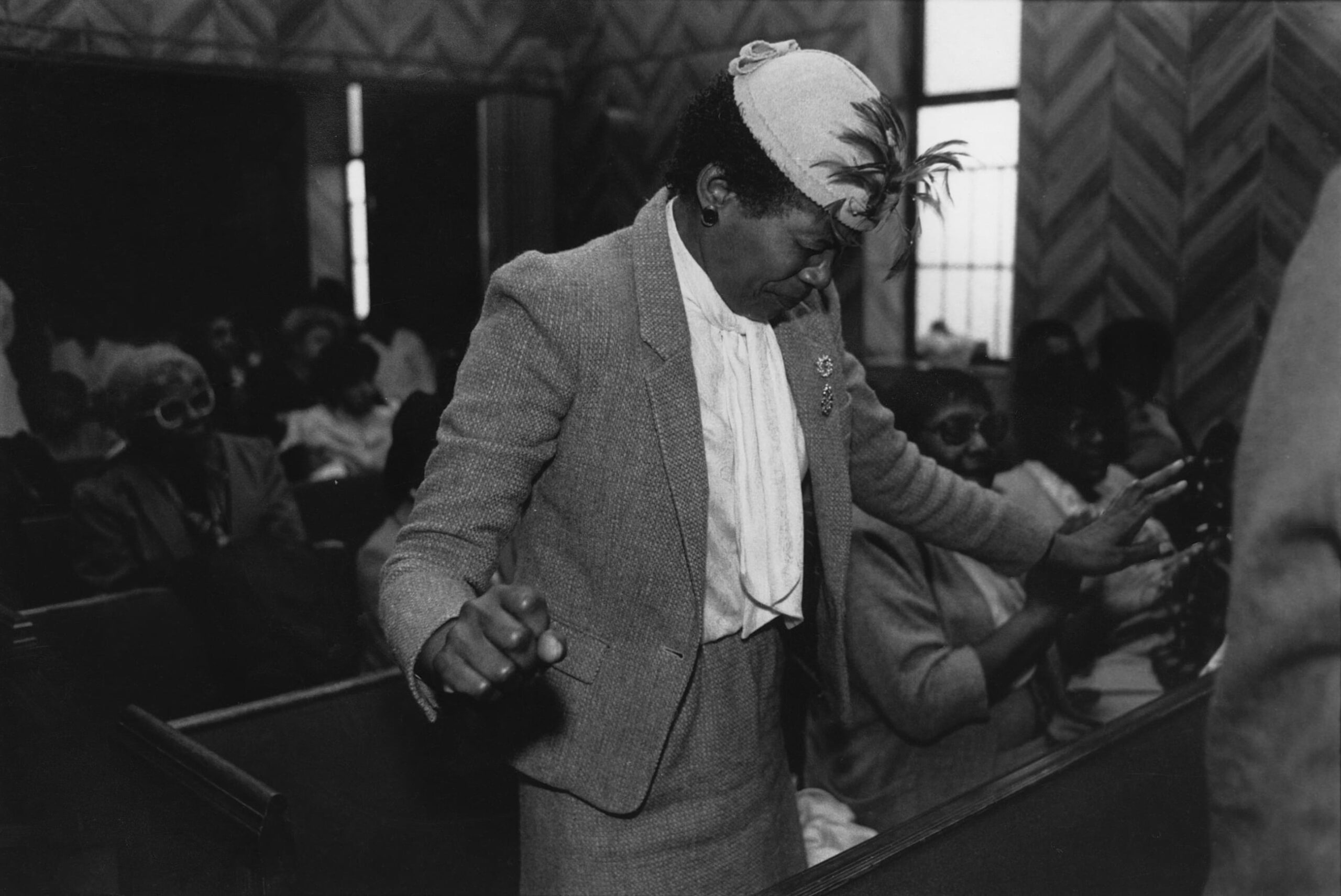

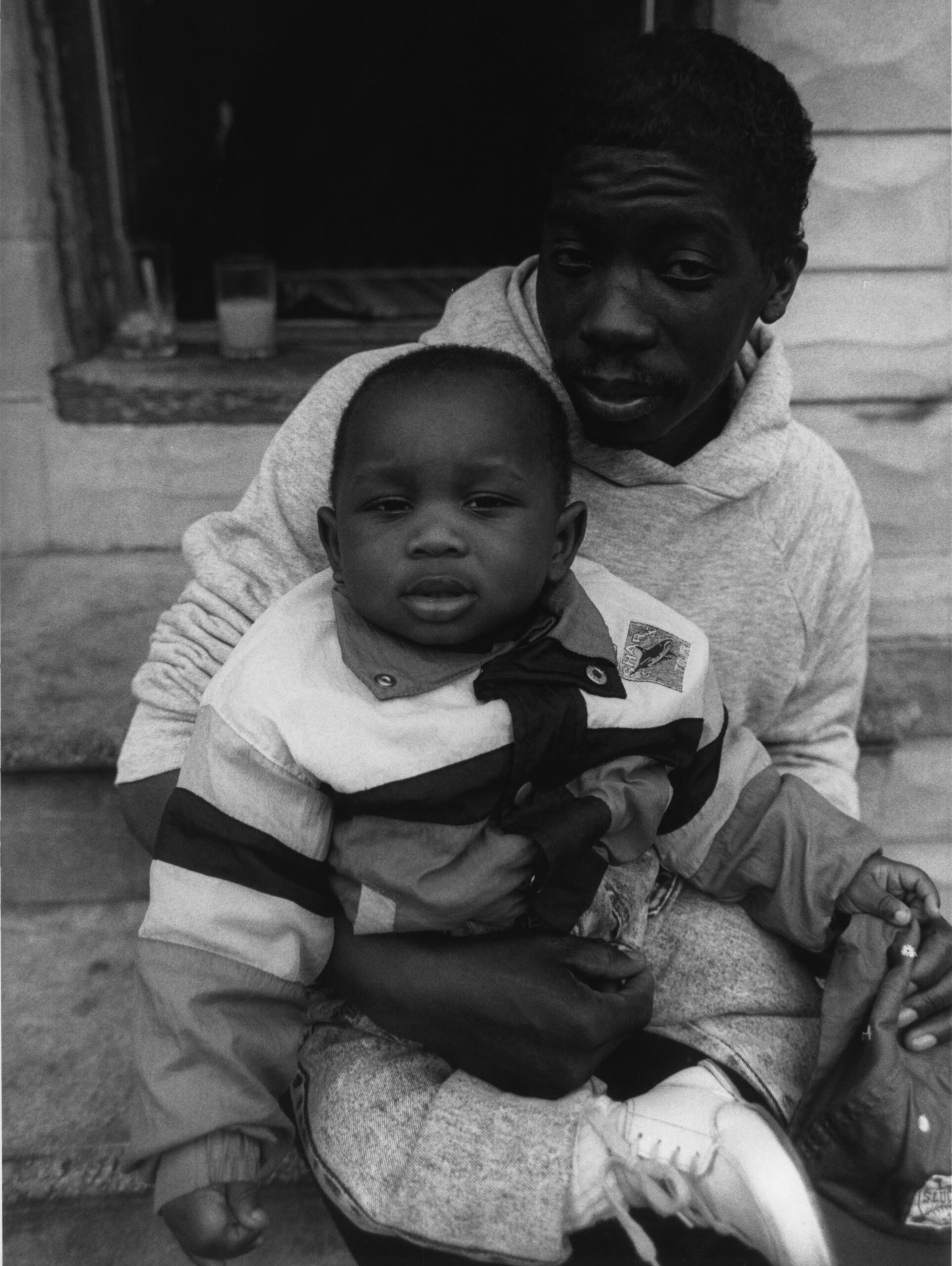

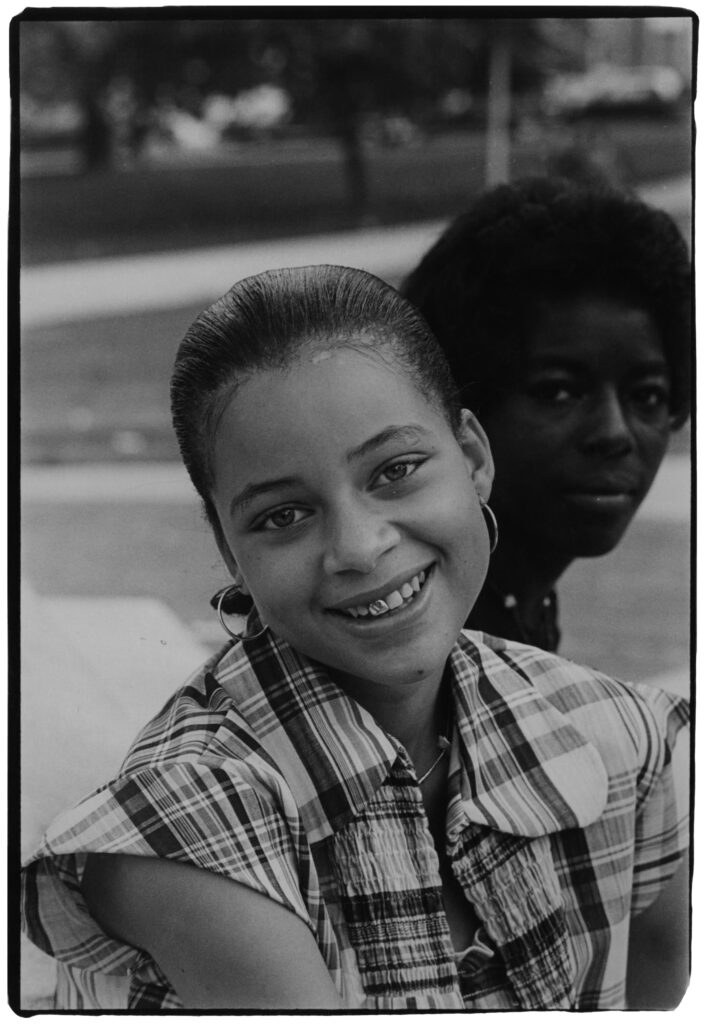

In conversation, Marcus Cuffie, son of photographer, the late Steven Cuffie, reflects on his father’s work and the importance of photographing “the center”. Featuring a collection of images illustrating what life looks like at the center of a city, with intimate portraits of Baltimore’s women and children, shot in Baltimore between 1974 and 1986.

Text by Kevin Quinn

Photography by Steven Cuffie

Issue 003

Steven Cuffie’s son, Marcus Cuffie, a stylist now based in New York City, recognized the potential of his father’s work first–the nuances of a work representative of a man and father with a nuanced life. Visiting his childhood home following his father’s passing, Marcus came across boxes and boxes of negatives. In those boxes, he found a retelling of his childhood, one in which his father was always taking pictures. Within the negatives that existed in those boxes, he learned new details about the life of a father who had always supported him and encouraged his own creative pursuits.

In October of 2022, Women, the inaugural show at New York Life Gallery, owned and operated by photographer and gallerist Ethan James Green, opened to great acclaim. Women, for the first time, presented a collection of Steven Cuffie’s work to the larger photography community, focusing on a curation of Cuffie’s images of Black women. In the aftermath of the fanfare, his son, Marcus, has worked to bring more of his father’s photography into the public light.

In the conversation that follows, Marcus Cuffie (MC) talks briefly with Citizen editor Kevin Quinn (KQ) to discuss his father’s work, the process of curating that first show, and what he hopes for the future now that the work has earned visibility.

“I can’t think of more than ten Black photographers doing this kind of work then.”

KQ: Tell me a little bit about Steven Cuffie.

MC: Obviously, he’s my father, born in 1949. From North Carolina, but he grew up in Baltimore. He was kind of the runt because all my uncles are 6’5”, 6’6” and 200 to 300 pounds. My dad was 5’7”, 5’8” but much more athletic. He was also born deaf in one ear. So he always had a different way of relating to the world. His father was an illustrator and sign painter during WWII. My grandfather and one of my uncles were the first people to introduce my dad to photography. So he definitely came from a family where it was supported more than normal. And that connected with me. My dad was super supportive of me pursuing the arts.

“He explored the relationship with sex within Black photography.”

KQ: Did you ever get the sense from your dad or uncles that this kind of artistic context was anomalous?

MC: We all have this understanding that it’s embedded in our DNA.

KQ: Wow.

MC: My dad was pretty lucky to think of art and photography as a career. You had Gordon Parks as an example, but he was an anomaly. And he was more of a journalist.

KQ: That’s right.

MC: To be fair, I think my dad did value photojournalists as photographers and saw himself more as a photojournalist as he got older. But the work I’ve been showing is from his late 20s to mid-30s. And it feels more artistic or portrait-based than his later work. He loved Dorothea Lang and all the farm security administration photographers of the 1940s. But he also loved Eadweard Muybridge, Alfred Stieglitz, and Man Ray. So he really did absorb photography as an art form as well as a tool for anthropological exploration.

KQ: How would you contextualize your dad’s work in terms of its sensibilities?

MC: The work that I first showed, which was all portraits of women, was really interesting because you don’t have a lot of Black photographers from that period who are known for documentation of Black women. Sometimes in an ironic sense, but also in an intimate, loving way. He explored the relationship with sex within Black photography. Those early images of Black women feel positive and they are beautiful, but they also speak to this intense personal relationship. A lot of the women he knew personally. Some were sex workers, some were girlfriends. There was my mother. Some women are more forward, some women are more nude. I don’t see work like that being made around that time. My dad’s other body of work is his photos of children. That was another interesting place to explore that wasn’t overcrowded in terms of Black photographers.

KQ: 100%.

MC: I can’t think of more than ten Black photographers doing this kind of work then. Baldwin Lee’s work is really amazing and similar, but he’s an Asian man coming to the South taking these photos and somehow getting more traction than the work of a Black photographer.

KQ: Yes. It’s “writing” from within versus using a voyeuristic lens. A very legible intimacy and idiosyncrasy that isn’t simply documentation.

MC: There is a closeness. My dad wasn’t from outside the city. You see the dilapidation and poverty in the corners, but the center really focuses on the individual, a Black person not as a myth—

KQ: Or archetype.

MC: Yes.

KQ: How do you see Baltimore’s place in your father’s work? If I think about images from iconic Black cities like Harlem, Detroit, and Chicago, there’s usually a sort of signifying that emerges about Black life. How is Baltimore different?

MC: Baltimore occupies this special place between the north and south. The speed and language and the way people relate to each other. And it has this freedom for an artist where you can live there cheaply and still get to New York because it’s only a few hours away. But you can be in Baltimore without the voyeurism other cities attract. My dad’s career speaks to that. In Baltimore, he was able to be a Black photographer making work about Blackness, not thinking about what people did outside of Baltimore.

KQ: Tell me about curating your father’s work.

MC: I’m still coming to understand my exact role in curating. First, I just took on the role of protecting the work. After my mom and dad died, the photos sat around for a while, and I didn’t want them to go to waste. Then I realized the photos definitely had a point of view. But I didn’t know where they would go; it was just a labor of love. Even after having the first show last year, I didn’t understand what they could mean to other people. And then when people saw the work it was amazing that they wanted to talk about it and were inspired by it. That’s what has motivated me: to produce more work and help expand or create a new conversation.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.