Ayo and Her Weird and Specific Things

Ayo and Her Weird and Specific Things

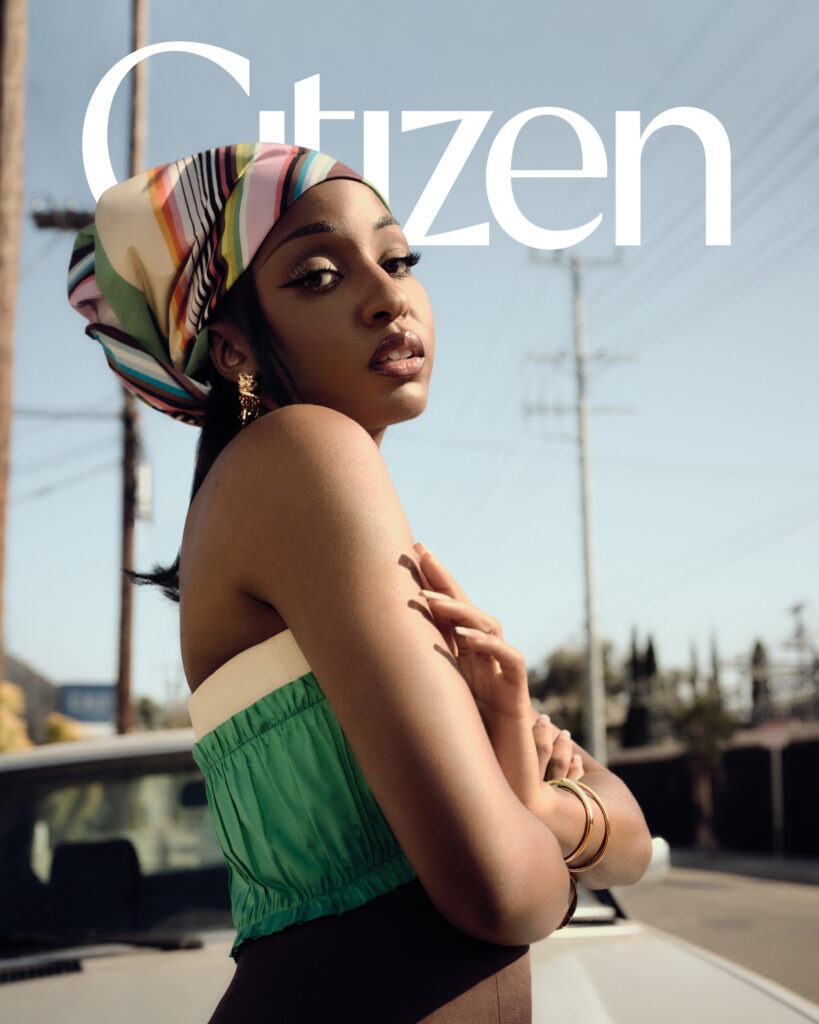

Text by Yaa Gyasi

Photography by Justin French

Issue 004

Ayo takes the call from the backseat of a car somewhere in London. This typically liminal space — between shoots and locales — stops being transitional and instead becomes another point of action. Such is life when you are it—smart, funny, fashionable, beautiful, a clear and shimmering star. And personable, too. This is evidenced by the grace she extends when I find myself having to hop off and back on because of technical issues, Luddite that I am.

I don’t interview a lot of people, and she’s been interviewed within an inch of her life. So, at first, there is some clumsiness and some wariness. But before long, talking becomes easy. I lose track of time and have to be reminded to wrap it up.

Our cameras are off, but I can easily picture her rumbling down cobbled roads, laughing generously or pausing to consider. At one point, she tells me that many of her comedy references are old, dating back to actors, movies, and comedians who pre-dated her existence. Growing up, her grandparents lived with her family, and so she spent a lot of time immersed in the things that elderly people enjoy. Perhaps this is why, by the end of our call, the thing that stays with me is that Ayo is unbelievably wise. An ancient wisdom wrapped into a kind of youthful angst. It is at once like she’s been here before and like we have yet to see anyone quite like her.

“I get to express myself through my work. My work is the thing. So I do the work. And then all of a sudden, it’s not about the work, and it’s about how people perceive you. It’s very, very strange.”

Ayo Edebiri (AE): Hello? [Silence]. I think you’re on mute.

Yaa Gyasi (YG): Okay. Okay. Sorry. I figured it out!

AE: Oh my gosh. Your voice is so nice. What a pleasant speaking voice. Oh my God. The power of an author.

YG: Oh. Unexpected compliments. Thank you. I appreciate it.

AE: You’ve never been complimented on your voice before?

YG: I actually have. I was trying to be humble about it, but–

AE: Yeah, you’re like, oh, this old thing, what?

YG: [Laughter]. Are we alone now? Did you leave?

Danielle [Citizen Co-EIC]: You’re not alone. I’m here. I’m just going to put myself on mute and let you guys chat.

AE: You’re never alone. Do you hear that sound from TikTok that’s like, “Black people, you’re never alone?”

YG: I’m not on TikTok. So I don’t know anything.

AE: It’s for the best.

YG: I used to have some social media, but now I’m just completely off. It’s good for some things and bad for other things. Like, I never know any of the references. I feel like I’m older than I am because of it. Do you know what I mean?

AE: Yeah. I’ve been off Instagram now for like three weeks or something [and] it’s honestly been amazing. But I think it’s true that it’s good for some things and bad for other things.

YG: I bet. Part of why I got off is because I was really overwhelmed after my first book came out. I felt so exposed. I can’t even imagine what it would be like for you.

AE: Yeah, it’s strange. The whole point of doing this for me, and I think for most people, is that I get to express myself through my work. My work is the thing. So I do the work. And then all of a sudden, it’s not about the work, and it’s about how people perceive you. It’s very, very strange.

YG: Yeah, totally. It’s like you lose your selfhood somewhat. People feel this entitlement to know everything about you or anything you post gets misinterpreted. It’s good to take a little break and to take some control back and decide if you want it again.

AE: Yeah. Yeah, we’ll see.

YG: Okay, I have questions, but let’s just have a conversation.

AE: Ask me anything.

YG: Okay. Where did you grow up? And what was the vibe? Was it the kind of place that you couldn’t wait to leave? Or did it feel like a place you’d want to stay or return to?

AE: I grew up in Boston. It was chill. I feel like it was like growing up anywhere. There were some things that were great, especially in hindsight.

YG: I know your parents were immigrants. Did you grow up as part of a little enclave of an immigrant community?

AE: Did you?

YG: I did when we first came to America. Well, I was born in Ghana and then we moved to America when I was two, and we lived in Columbus, Ohio. Which at the time had so many Ghanaians. So, in some ways, it felt like a very soft landing. It felt like Ghana light to me. My dad’s a professor, and so he was getting his PhD when we came to America. So, we moved every couple of years as he looked for a tenure-track job. Each place we moved to there were fewer and fewer Ghanaians. And then by the time we got to Alabama, there was like one Nigerian family that we’d have to drive like 45 minutes to go see. But my parents clung to that because they needed it.

AE: Yeah. Yeah. Well, my parents emigrated separately when they were teenagers. They are from two different places, Nigeria and Barbados. So they’ve been in America for a bit. My family is very large on both sides. And they both have a lot of siblings. And then those siblings all have a lot of kids. And we would all just like spend a lot of time with each other.

And my grandparents lived with us. My grandma would cook Nigerian food and my mom would cook Bajan food. My mom is an amazing chef. She’s also a very proud Bajan woman. Same with my dad. It’s like these two very proud people married each other and broke down each other’s walls.

YG: I mean, it’s good that they were able to kind of cross those bridges together.

I had my first job at age 15. My mom was a CNA [Certified Nursing Assisant] so she got me my first job as a waitress in a retirement home. So I spent most of my days with elderly people who are like coming down for their dinners at five o’clock. I got so close to some of them. And now that I have a kid — I haven’t mentioned that yet, I have a daughter who’s turning two — I’m so obsessed with the idea of her having those intergenerational relationships in her life because, unlike me, she’s going to be around grandparents and cousins like you, rather than elderly people in a nursing home.

AE: I’m an only child. And so I’m always like, well, I guess if I have a kid they’ll have to have found family. But I actually love old people. A lot of the references that I have for comedy — 100 years in the future, somebody will find this interview and be like, oh, that makes sense — all the things that I want to make are so inspired by a love for like Monty Python and old sitcoms. I love silent films. I love Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin. I love just hanging out at a bar and meeting an old guy and being like, all right, we’re both gonna have like the best conversation of our lives, and be crying at the end of it–

YG: [Laughter]. Have you read ‘Swing Time,’ the Zadie Smith book?

AE: No. It’s in my library and I haven’t read, yet.

YG: It’s okay. You’re just saying that you love — like that you have these old references made me think of that book because I feel like it’s kind of an homage to a time of singing in the rain, like that kind of a feel but obviously modernized.

AE: I’ve only read ‘White Teeth’. One day, one day in my life, I’ll get a month off and I’ll be able to read again.

YG: But what have you been reading lately?

AE: Let me look into my tote bag right now. I’m finishing this book called ‘The Details’. I went to a bookstore and I just picked up a lot of like translated books. I just finished ‘The Details’. It’s by, I’m going to mess this up, I-A Genberg.

I was reading a lot of Tove Jansson’s short stories. I read her short stories and I’ll read 10. And then I’m like, I read a book, I can read. I’m a good person.

I’m also reading ‘Pastoralia’ by George Saunders. Because I really loved ‘A Swim in the Pond’. And I’m really into ‘[Lincoln in] the Bardo’. And I was like, alright, you’re my boy now. It’s on.

YG: He’s so singular that you can always tell when he’s somebody’s influence, which I find really fascinating.

AE: Ooh, well I hope he’s one of mine. He reminds me of like a literary Charlie Kaufman, where I’m just like, you kind of think like a little freaky boy. And like, you popped off and got establishment recognition after you were kind of always doing your little freaky thing. And then you’re like, here’s more freaky [stuff]. And everybody’s like, I mean, yeah, I guess.

YG: There’s a book that I love by this writer named Hisham Matar. It’s called ‘The Return’. He’s a Libyan writer. And this book is kind of about exile and his father.

AE: Oh! I bought that book at the bookstore. And I’m very excited to read it.

YG: It’s so good. It’s so good.

AE: Shout out to Daunt Books and the guy who helped me. I hate that I forget his name.

YG: We’ll shout him out. The book is lovely. There’s a moment where he’s talking about how he goes to museums and will sit in front of a single piece for the entire time.

AE: I love that. I love museums. Growing up in Boston, it was a very museum rich place. And then going to school in New York and especially like being a student there, you get to go to so many museums for free. I find museums to be like very life affirming, weirdly, even though it’s like these relics. But I find [museums] really, really beautiful. Now that I’m in London — shout out to colonialism and shout out to the diaspora — I have been going to weird museums, like very specific, strange museums, like the

Sir John Soane or the Musical Museum in Brentford, which is entirely dedicated to automated musical machines throughout history. So weird. Literally had a blast.

YG: So strange and specific.

AE: That’s where I get a lot of my inspiration, weird specific things. Even if it isn’t a direct source of inspiration, I think seeing somebody else do their weird specific thing is affirming in that it reminds me that there’s space for me to do my weird specific thing.

YG: 100%. You can’t know how what you see is going to contribute to your work, you don’t know how it’s going to come back. I mean, I think that’s like one of the most beautiful things about art making, that it just all goes in. Everything goes in.

AE: A few years ago, I was doing some standup with Jacqueline Novak. She’s an amazing comedian. She had a show called ‘Get On Your Knees’. After a show we took a walk and we were just talking and she was like, “I can already hear the critic being like, this is so specific, or why is she talking about this? — another female sex comedian, blah, blah, whatever.” But she was like, “I just had to keep going, like I had to keep diving in. And now the show is becoming an hour of me talking about — spoiler alert: blowjobs. But, I have to keep doing that because I realized that in all the years I’ve been doing stand up I’ve kind of just been in conversation with myself about all these topics.” You, the artists, are having a conversation with yourself.

The things that I write for myself, the things that I want to develop, they’re different. But I can hear the conversation I’m having with myself about the things that I’m very interested in. Do you feel that way?

YG: I definitely do. Writers get this question all the time: who is your audience? And the only real answer is yourself. And it feels like a lazier, like cheating answer. And it’s not the answer that people want to hear.

AE: It’s a bad question.

YG: Yeah, the only person that I’m writing for or toward or thinking about is myself and my own little intricacies and curiosities and obsessions. And I really only have three or four things. So it’s all the same.

AE: For me, what are the things? They’re all weird, they’re all specific, but they do percolate around the essential fascinations and anxieties.

YG: The magic is that you can continue to make work around those three or four things. It just proves we’re endless. Like we’re all just endless.

AE: I was told once by a reflexologist that this was one of my last lives, if not my last one. So sometimes I’m like, maybe it is, because I actually do identify as really full of shame all the time. But I am like, life is so long. And weirdly, a career is even longer. I think social media has like warped our brains with regard to time. I think it’s really damaging for artists to engage with it beyond a certain extent.

But then again, careers are long and I look at other people taking that into account. Careers are full of ups and downs.

YG: That’s so generous and something that I don’t hear people say a lot. It’s not something that I let myself feel.

AE: I let myself feel it all the time because also I think, especially like as an actor, and this is a thing that is very new for me because I’m not an actor by, by, um—

YG: Were you about to say by choice?

AE: A little bit. That wasn’t what I thought my path was gonna be. I was planning to be a writer and a comedian and so I think the way that I approach things also is as a writer and a comedian and not as an actress — specifically an actress in a female presenting body, especially a Black woman’s body, I’m like, whoa, this is vile. And I did not consent to this.

I have the mind of a writer and of a fool. And I speak like a fool. I want the jester’s privilege. I miss the jester’s privilege.

And instead, it’s like, ah, you’re a lady ingenue. Or you’re the Black girl that people think X, Y, Z about. And I’m like, none of it is true. I can’t. I just cover my ears because life is long, and a career is magically even longer.

YG: Yeah.

AE: Did you see Maya Rudolph’s interview in — I think it was in the New Yorker. I think. She talked about the cycle of media over time. You used to do a show and it would be in the conversation for months. There was this slow seep of culture versus now. Now, it’s like, oh, maybe somebody comes and talks to you on say a Monday or a Tuesday. But by the next week, it’s like, it’s already gone.

YG: I remember interviewing Kazuo Ishiguro for his last novel, ‘Klara and the Sun’—

AE: Okay, jealous. Wow!

YG: Something he said that really stayed with me is that the quality that he’s most interested in when writing is that his books linger and that there’s this residue so that when you like close the book, you’re still thinking about it. But that’s the goal of the work. No matter what he’s writing, what he’s trying to get is that lasting power, that lingering, that residue. And it feels like there are so many things now that are built around this kind of quick satisfaction —

AE: Yeah. They are not made to linger. They’re made to zap you in the brain and stun you. And like stupefy you, or enrage you or make you feel crazy so that you’ll talk about it. I actually just stopped watching things that are bad.

YG: I commend you, that’s so hard.

AE: Instead, when I have energy, I’ll try to do something that will give me peace.

Also with friendships, I’m now where I’m like, ‘oh, we had a friendship for which the bedrock was trash or whatever’, and I just say I don’t want to engage in that anymore because I’m thinking of my — not just my artistic practice, but my own sanity and living.

YG: Wait, that is so revolutionary.

AE: You end up missing out on things, 100%. But maybe your peace is valued higher.

YG: Yeah. I’m so moved by that and so impressed by that because I feel like it takes a long while to reach that understanding for a lot of people. Some people don’t ever get there.

“I think seeing somebody else

do their weird specific thing is

affirming in that it reminds

me that there’s space for me to

do my weird specific thing.”

YG: Do you still do stand up? I mean, you said you did a show recently, but is that like a thing you return to when you want to feel that sense of like, I don’t know, like coming back to yourself?

AE: It’s also about connection with an audience. Live performance and live theater was like my first way into all this. I think that’s just my first love, that and writing. I just I haven’t had the time to do it as much, but it’s a part of my practice.

YG: Are you writing things for yourself?

AE: Yes, but not like for myself as like an actor necessarily, but like, in my own time and things that I want to develop and such and such. Yeah.

YG: Do you think there will be other forms that this creative writing might take?

AE: Absolutely. But I could never write a book. I don’t think.

YG: I don’t believe you. I feel like you could. Even just talking to you for this short amount of time, I’m like, you have a book.

AE: Well, I would have to disappear for like 25 years.

YG: “A career is long.” I can also recite that to myself on the days where I feel like I should be going faster. Because I’ll tell you, having a kid, your relationship with time is so, so different. I feel like I’m always just stealing timing for myself to be able to write. It has to come from something else. So my relationship [with writing] is so different from when I was younger and it was the only thing I had to do. I was really fortunate, I went from college to grad school to having my first book out. So I never really had to balance writing and another job.

AE: The kid for me is my acting career!

YG: I think we’re out of time.

AE: Oh.

YG: Thank you. I mean, I’m obviously, I’m doing this because I’m a huge fan of yours, too.

AE: I’m actually doing this because I hate you, so — No, I don’t know why I’m here. Fine, it’s because I’m such a fan and I can’t wait to see all of the things that you do.

YG: Oh, me too, me too. It was really nice talking to you. Enjoy your break. I’m glad we were finally able to do this.

AE: Me too. This will brighten up the rest of this gray day here.

YG: I think a similar thing will happen for me, too.

Correction (October 24, 2024): An earlier version of this article incorrectly ascribed the quotation “And now that I have a kid — I haven’t mentioned that yet, I have a daughter who’s turning two” to “AE” (Ayo Edebiri) rather than the speaker “YG” (Yaa Gyasi). Ayo Edebiri does not have a two-year-old daughter; Yaa Gyasi does.