A Brief Case: Janicza Bravo has “range”

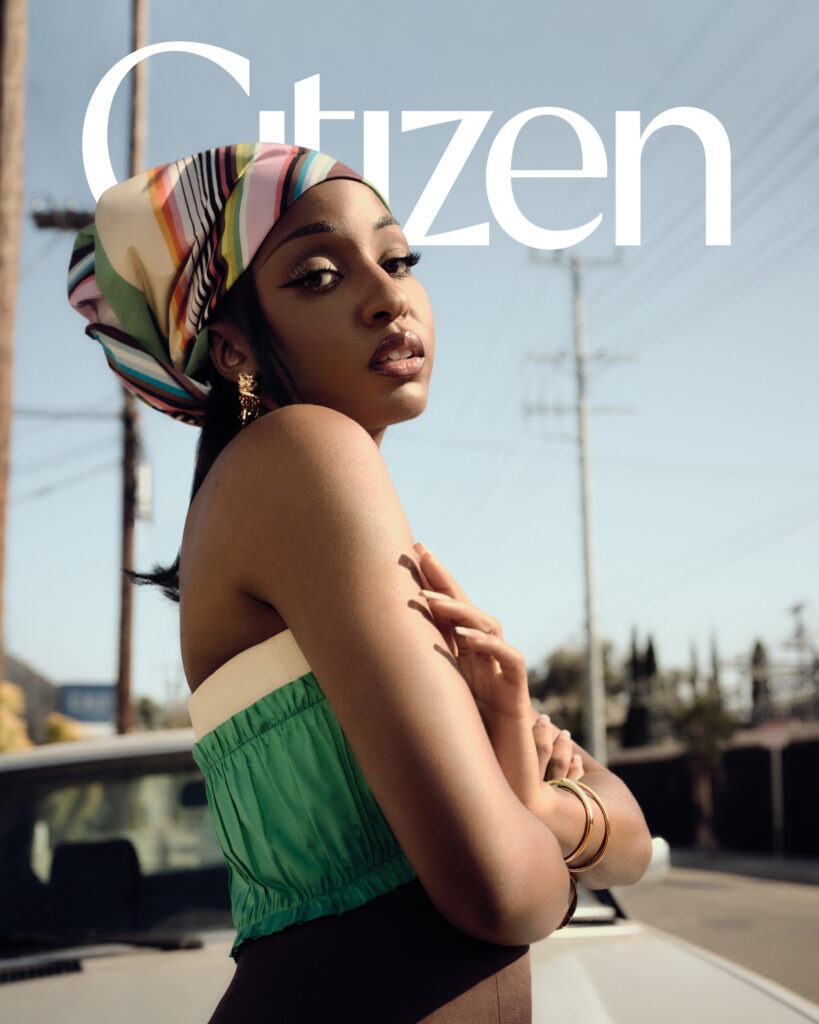

Citizen’s Creative Director (HG) chats briefly with film, TV, and stage director Janicza Bravo (JB) about her latest project, “Listeners,” the bullshit of “the only” and maintaining “range” within your work.

In conversation Janicza Bravo and Henrietta Gallina

Illustration by Shayla Hunter

Issue 004

“I thought you’d really made it if you were the only one, and now I’m like, that’s fucking bullshit.” – JB

Janicza Bravo has range and admits that she aims to maintain that “can’t pin me down” range for the time being. She is one of those people who may have lived many lives or perhaps lives a life so individually led that it is hard to pinpoint exactly where the Janicza that currently exists in our collective psyche began. The Janicza that the public first got to know, or at least the larger public that revolves around the world of film and TV making, seemed to be avoiding the fate of being boxed in early on with her feature-length directorial debut, “Lemon.” “Lemon” is the sort of dark comedy with an ensemble cast that rarely signals that a Black woman is behind the camera. Janicza’s next feature film, “Zola,” directed by Janicza and co-written along with playwright Jeremy O. Harris, had its world premiere at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival, where it was nominated for the Grand Jury Award. Zola, too, represented a seriously dark comical storytelling that interwove a nuanced and unique representation of a Black woman that the majority of filmmakers lauded today would not be able to achieve. Since the release of “Zola,” Janicza’s name has escaped the world of film and TV and floats in the ether of the everyday cultural zeitgeist. She is now the sort of director who appears on magazine covers and elicits a kind of curiosity about her own life and career most often reserved for the actors she directs. Shortly before the release of her latest project, “The Listeners,” Janicza chatted briefly with Citizen creative director Henrietta Gallina, exploring some of our most delightful curiosities about her, where she has been, and what she will do next.

HG: Hello, how are you?

JB: I’m really, really good.

HG: You look really well and hydrated and glowing.

JB: Thank you. You look pretty hydrated yourself. Skin is killing it. I had kind of a funky morning. There’s a few things I’m working on, not as a director, as a producer, that are in different stages of getting made. And it’s so emotional, and there’s so many feelings. But by the time you get to the end of the road, if you look back, the amount that you’ve gone through is so wild that you can’t wait to do it again.

HG: It’s like childbirth. It’s like creative amnesia. And I think that’s what we need to keep going.

JB: But it’s brutalizing. You forget how much labor goes into producing the work. The amount of hours, right? And when you’re working with a group of artists, I don’t know that they’re fully clocking how much of yourself you are pouring into their making. I guess it’s like parenting. I don’t have a child, but it’s really thankless. What I’m dealing with is, do I like that I’m a person who wants to be thanked? I might be a person who needs a thank you, which is a weird thing to admit.

HG: I think that’s human nature, though, because when you put something before yourself—whether it’s a project or someone else’s feelings or a child—it’s not so much that you always want a thank you. I mean, obviously, it’s great to get a thank you and all of that, but there is an unspoken thanks that can manifest in different ways, like in how people show up. There are just certain cues that you often want to receive that let you know that it’s not untethered, like, I see you, thank you, and it doesn’t always need to be verbal.

JB: Some sort of awareness, some reciprocation, right? An acknowledgment. I’ve hesitated for a while to get into making other people’s work. The toll is quite exhausting.

I read this article, I’m forgetting the filmmaker now, but he had made a feature. It was his first, I believe. And it was a really small movie. And it sold really well at Sundance. Then he was going off to make this massive movie. So he’d made a movie that was like under $3 million and now was making a movie that was like $170 million. And in the article, there is this quote from, I think it’s JJ Abrams or Steven Spielberg, that’s like, “I’m sitting in a room and I’m looking at this guy. This guy is sitting across from me. He reminds me of me at that age. He’s got the baseball cap on, and I just see myself in him.” And I read that and I thought, that is never going to happen to me. And so I had this feeling that if I ever got the chance to, if I could ever do that in some way monetarily, I ain’t got it like that, right? But if I could ever creatively do the thing of looking at someone and seeing myself in them and being like, I want to help you because I think I can, that I shouldn’t walk away from that.

HG: That is really selfless, though.

JB: I feel I was raised right at the end of this moment where there was room for only one. And so I find myself in these two lanes where there’s room for only one and where I could rewrite that narrative. And I really had to work through the pleasure of there being no other me’s in the room, right? That I was winning if I was the only one. I was like, what the hell is that? But I thought you’d really made it if you were the only one, and now I’m like, that’s fucking bullshit.

HG: Yep, it’s the old guard, the gatekeepers who anoint you and make you feel like that’s when you know you’ve made it. What I think is beautiful in a lot of your work, though, and even on Instagram and seeing how you move through your personal and professional life quite seamlessly, is this sense of community, you know, in the way that you collaborate with people, in the way that you develop friendships within a collective and oppose the divide-and-conquer strategy that was set up for us.

JB: Totally.

HG: Ok, we need to reset here – I’m really excited to talk to you, especially for this STRANGE WORLD issue, which is, in essence an ode to the Black female experience. Thinking through the good, bad, beautiful, and brutal. But in the more traditional sense of the theme, you do operate in that space of strangeness. The dark comedy and fantastical elements that show up in your work. So, could you introduce yourself and then talk a bit about where you grew up? I’d love to know where some of that magic comes from.

JB: Absolutely, I’m Janicza Bravo. I was born in New York and spent the first few months of my life there before moving to Panama. My parents are Panamanian. My mother, my father, my stepfather. I lived there until I was 12. Then I moved back to New York. During those 12 years in Panama, there was a little break where my family moved to the south because my mother was in the military. When I look back on that time now, there’s so much fondness for it, but I didn’t necessarily appreciate it growing up inside of it.

HG: I feel like that is a common theme when we often talk about our childhoods or our experiences growing up. Not appreciating the things in the moment and then seeing them for what they are in hindsight.

JB: Absolutely. I think also that because I was born in New York, I always knew it to be a part of my story. But I was living in this really small city, small town in Panama, for a bit. There were monkeys outside the patio stealing our food and sloths and capybaras in the backyard. And I was like, “What is this?” I felt like I was in the fucking jungle because I was. And I’d been to New York a bunch in the ‘80s, and it was the coolest place I’d ever been to. That New York doesn’t exist anymore. I found myself longing for that and not appreciating the sort of pastoral place that I had come from. But I am an only child, and we moved back to Panama so we could take care of my grandmother. So, I was raised primarily by my mother and my grandmother because my parents were not together when I was born. But they got back together and married when I was 12.

HG: My goodness, that’s so romantic!

JB: My mom and stepdad were together until I was 12. And then, my mother remarried my father. So I really met my dad when I was 12. My parents are still together now. They have a kind of telenovela love story. They’ve been in each other’s lives since they were children, but now they’re together. I had not met my dad consciously till I was five. I was in a car with my stepfather, and I think he and my father got into some kind of a fight, like a true classic Latin telenovela. And we drive through this neighborhood that’s pretty dodgy. And he said, “Do you know who that man is?” And, I was like, “I don’t.” He says, “That’s your father.” That’s how I met my dad. I’m five, and I’m sitting in the front seat of my stepfather’s Jeep. And then my father walks up to the window.

HG: Wowzer! And your mum and dad reuniting, how romantic!

“I think my sense of humor or my attraction and draw to absurdity had so much to do with the people who were around me who were really not responsible with their feelings.” – JB

JB: Oh, it’s so great. I love it. I really do. I think my sense of humor or my attraction and draw to absurdity had so much to do with the people who were around me who were really not responsible with their feelings. They had lots of very big feelings that were constantly on display, and they had not done the most solid job of being aware that there was also a child there.

HG: A lot of creatives have similar experiences of growing up with various stimuli that are often lacking boundaries, particularly in the formative years, when your imagination, your sense of self, and your sense of play develop. So, it does make sense that your brand of dark humor culminates in something that’s still very intelligent but also quite emotionally big.

JB: I buy that.

HG: Yeah. Like when I think about “Zola”, and also the work you’ve done with projects like “Atlanta”, I can now imagine you sitting in a car with your stepdad and dad and saying, “You know I’m five, right?” Constantly tapping into an augmented reality because it’s really happening but not necessarily in the realm of your understanding.

JB: That’s totally right on augmented reality.

HG: I would love to know more about your new project, “The Listeners”. Obviously as a Brit, I love a bit of BBC. How did this project come to pass?

JB: Gosh. I think two years ago I got sent the script for the first episode. It’s four episodes. The BBC version is four episodes, but the international version is five. So, I got sent the script two years ago for the first episode and then an outline for the series. And I read it and was really immediately into it because it felt so perpendicular to what felt like the right thing for me to do next. I have a pretty decent career in television in that I work a lot, and I have been offered a lot. And then this show came along, which ultimately felt like making a film. And I am, first and foremost a theater director, though I have not directed theater in a long time. But it felt like going back to my roots, which were more drama-leaning and very actor-centered, performance-centered, straight, slow drama. I felt like people didn’t necessarily know that I could do that, that it was available to me, right? And so it felt like an opportunity to flex a muscle that I hadn’t worked out in a while.

HG: Can you tell me a little bit about it?

“[‘Listeners’] is very adult and very elegant, which are not words that I usually associate with myself as a filmmaker. I wanted to ground myself a bit more here.” – JB

JB: Yeah. So it follows this woman, played by Rebecca Hall, who starts to hear a sound that seemingly no one else can hear. And then a student of hers–she’s a school teacher–also hears the sound, and the show follows the rise and fall of them getting close. 40-year-old women are not supposed to be friends with 17-year-old boys for lots of reasons. And one of the big draws for me was that the show has all the things you think are wrong and it is constantly inverting what you think is meant to happen. I got really excited by that. It’s very adult and very elegant, which are not words that I usually associate with myself as a filmmaker. I wanted to ground myself a bit more here.

HG: I love that you have range, which is really what it comes down to.

JB: I wanted to show that I had range because there are not a ton of people who look like me who are doing this. And I think that the people who do look like me who are doing this, whether or not they want to, are constantly being boxed in. And I just decided I wanted to write my own history.

HG: So I’d like to pivot to some quick-fire questions. First, I’d like to ask what you’re reading at the moment.

JB: Oh, that’s so good. I’ve got two. Well. I’m hesitating because they are things I’m adapting, so I’m a bit hesitant to name them.

HG: Ok. What have you read recently that you would recommend that I read?

JB: Yeah, thank you!

HG: I’m not trying to blow your shit up!

JB: I’m gonna say “The Visible Man” by Chuck Klosterman. I just finished it. I don’t want to tell you much about it, except it centers around a therapist and her patient and the places they go that they shouldn’t go.

HG: I’m gonna check it out. I love that you are a low-key, high-key fashion girly.

JB: I love wearing clothes.

HG: You do have a great sense of personal style. I love how you put outfits together. The way you experiment with accessories and shape, a little Simone Rocha moment, and I know you love a bit of Patou. So, super random question, but if you were to live in one outfit that you’ve worn before forever, what would it be?

JB: I know exactly what it would be. It would be slacks. It’d be slacks with some kind of probably solid color socks. So, say it were a khaki slack or probably white slacks, cause I really like white bottoms. Probably a white t-shirt, a chambray shirt, and a navy jacket. I’d probably go for a mid-weight blazer if I was gonna wear this always. And then the socks would be like royal blue or tomato red. And then I would wear, part of me wants to say it’s a loafer, but I think I should probably do like a clog because I think that if that’s forever, that’s probably gonna feel better on my foot.

HG: Yeah, I think the clog feels the most correct for you.

JB: The clog, yeah. I think like a lifetime, wearing loafers would be really bad for these arches, you know?

HG: The last question I’ll ask you is, what is a place you have been to that has really moved or changed you?

JB: Oh, that’s so great. That’s such a good question. Gosh, there are a few of these. I would say the one that comes to mind is Mexico City. I went to Mexico City many years ago, soon after my husband and I separated. And I had this eat, pray, love experience, or I think it was supposed to be like an eat, pray, love experience. And I felt like I really belonged there. I really found myself there, and I dream and fantasize about being able to go back and have this decent period of life there.

HG: I love that for you so much! It’s been a joy speaking to you. I’m really excited to watch “The Listeners”. I love this quote from you about it: “Having an experience that others cannot relate to is not foreign to me. While I may not hear a sound that others cannot hear, I’m undeniably walking a path that many cannot see. Claire’s journey mirrors my own.” I think reading that felt so relatable. I think it’s universal.

JB: I can’t wait for you to see it. I’m excited. Perhaps our paths will cross in the flesh sooner rather than later.

HG: I only hope so, really.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.