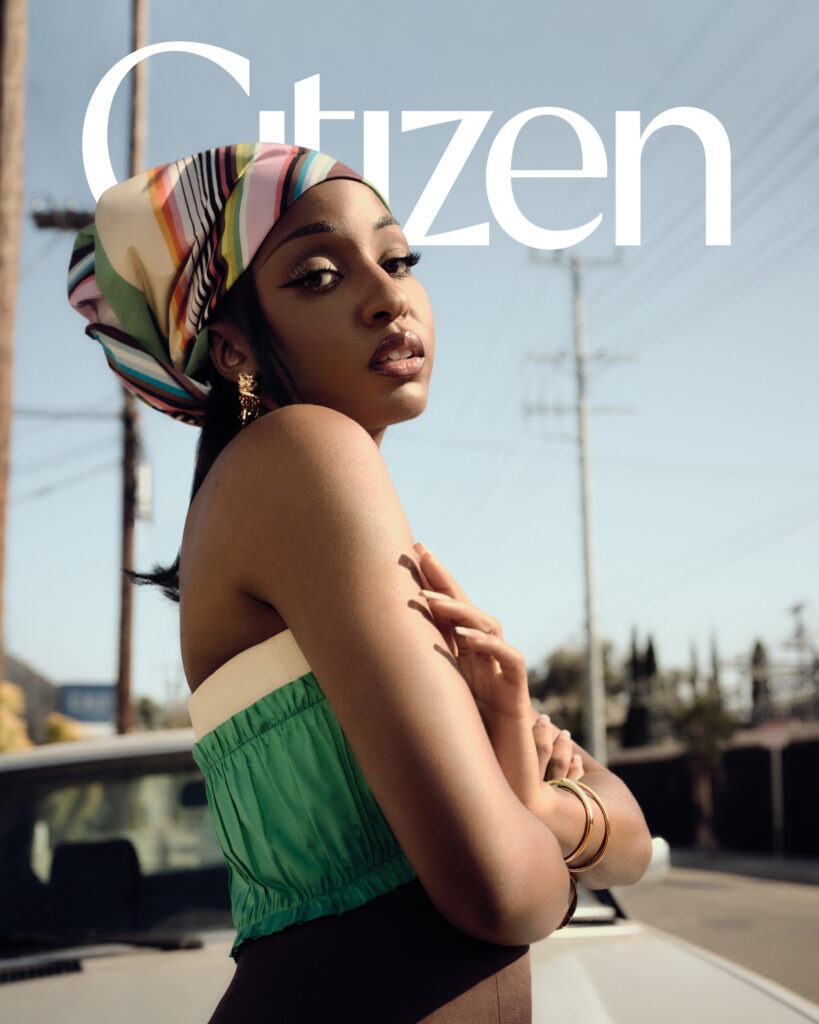

A “Promising” Artist: Khadija Saye

Text by Citizen Editors

Images courtesy of the Estate of Khadija Saye

Issue 004

In a celebration of Khadija Saye, a “promising” photographer and visual artist, we present her last collection of images.

“This work is based on the search for what gives meaning to our lives. “

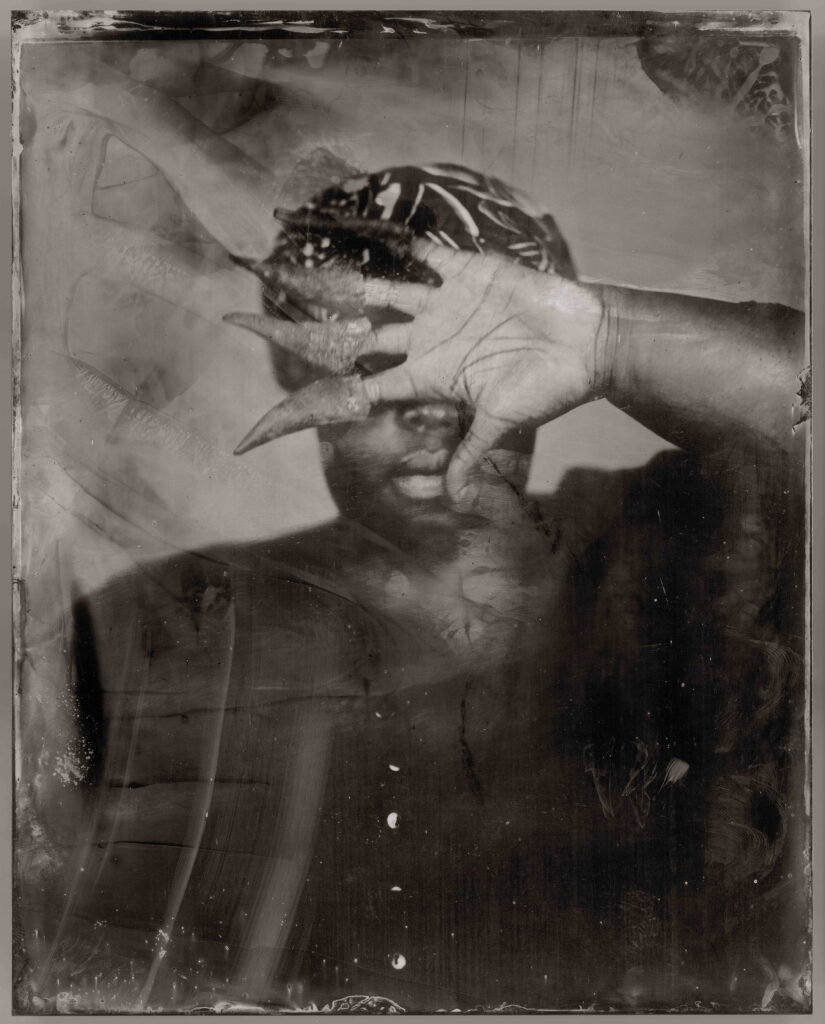

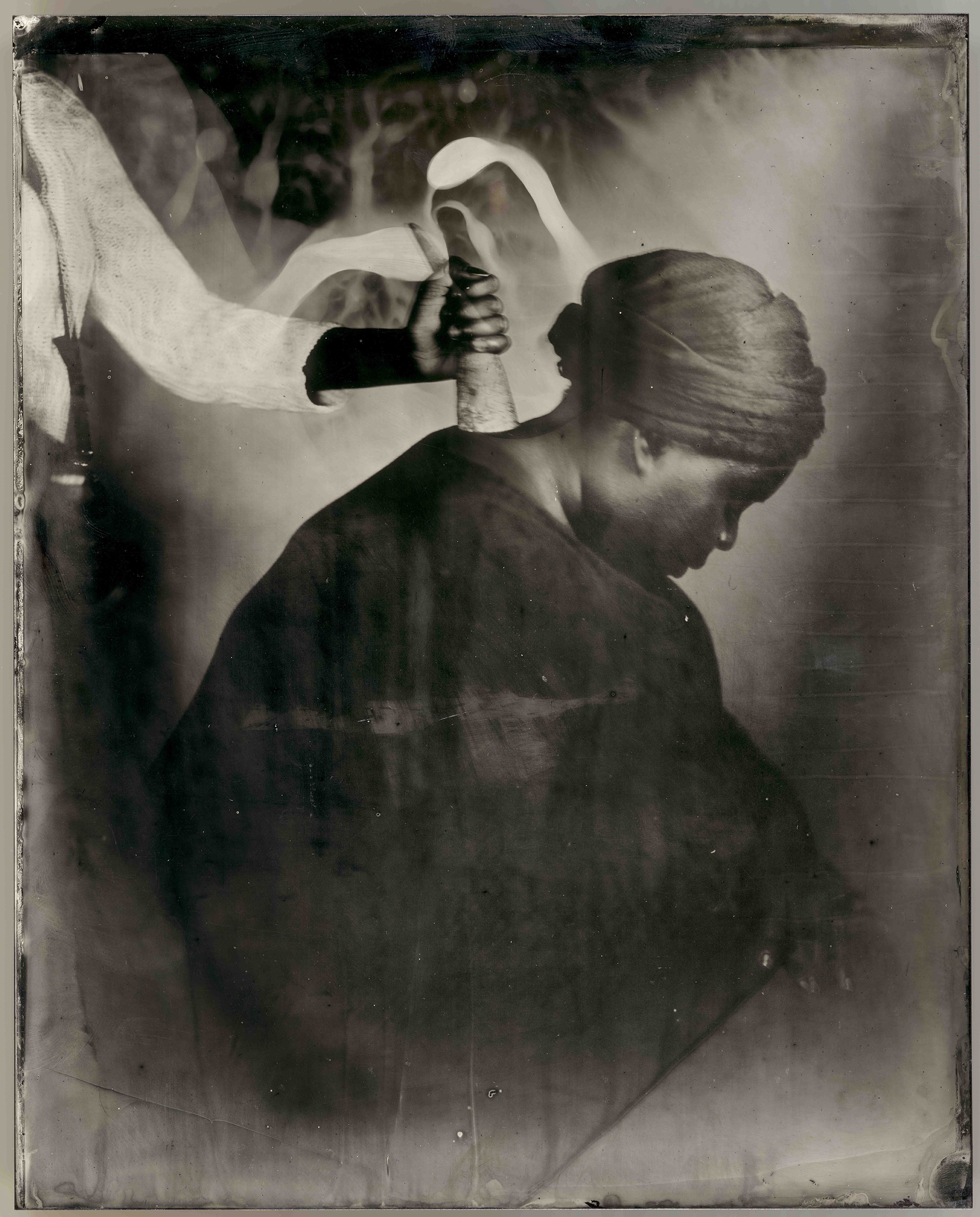

An Editor’s Note: The image on the page that precedes this text and the images in the pages that follow are the work of Khadija Saye, a Gambian-British photographer described in Tate’s 2016-17 report as an “artist at the beginning of a promising career.” Khadija created this series to be featured as part of the Diaspora Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2017. Titled “Dwelling: In This Space We Breathe,” this collection consists of eight tintype photographs prominently featuring the artist. In the text accompanying her display of a portion of these works in 2017, Khadija noted:

“The series was created out of the artist’s personal need for spiritual grounding after experiencing trauma. This work is based on the search for what gives meaning to our lives and what we hold onto in times of despair and life-changing challenges[…]Whilst exploring the notions of Gambian rituals, the process of image-making became a ritual in itself. The journey of making wet plate collodion tintypes is unique; no image can be replicated, and the final outcome is beyond the creator’s control. Within this process, you surrender yourself to the unknown, similar to what is required by all spiritual higher powers: surrendering and sacrifice. Each tintype has its own unique story to tell, a metaphor for our individual human spiritual journey. The process of submerging the collodion-covered plate into a tank of silver nitrate ignites memories of baptisms, the idea of purity, and how we cleanse in order to be spiritually sound.”

” The next chapter for me is to continue to bring up these questions. “

As is true of art, these images vividly reflect the artist, her heritage, and her hopes.

Born in London to Gambian parents on July 30, 1992, Khadija lived and worked in a 20th-floor flat in the Grenfell Tower block in West London. Having attended a local school at age 16, Khadija earned a full scholarship to the prestigious Rugby School, where she, with encouragement from her teachers, studied photography. She went on to complete a degree in Photography at the University for the Creative Arts in Farnham, graduating in 2013.

In 2017, Khadija was selected to exhibit her work as part of the Venice Biennial Diaspora Pavillion, the first major international exhibition of her work. On the morning that Khadija was to present her collection of images in Venice, she, in an interview with BBC Three, described her internal transformation: “Waking up this morning was very strange because I woke up to people speaking Italian outside my window and it just clicked, ‘Oh, no I’m not at home,’ I’m not in Ladbroke Grove anymore. And one of my friends said, ‘You’re an artist.’ And I was like, I am now.” Khadija had become the thing she intended to be, and these images are evidence of that.

If you were to, upon seeing these images or hearing about Khadija, follow that insatiable instinct to see more, search and find as much as you can about this young woman transformed into an “artist,” you would quickly realize that a search of Khadija’s name reveals a truth that quickly extinguishes the hope you feel for more.

Khadija Saye is no longer here; she is no longer full of all that promise that critics raved about in 2017. Instead, her name is most often sandwiched between words that describe the tragedy that took her from us. “Among the victims, my kind, funny friend Khadija Saye, and her mum,” is the headline that sits atop an essay published in The Guardian, penned by Sanaz Movahedi, a fellow artist and friend of Khadija’s.

On June 14, 2017, a fire broke out on the fourth floor of Grenfell Tower, a public housing block in West London. Flames quickly engulfed the entire tower due to the building’s highly flammable exterior cladding. Khadija Saye, a resident of Grenfell Tower, was at home on the 20th floor with her mother when the fire broke out. She was among the 72 people who died in the tower that day. She was only 24-years-old. At the time of her passing, six photographs from the series she had been so excited to exhibit for the first time were on display at the newly opened Diaspora Pavilion. Seven years after flames engulfed Grenfell Tower, a public inquiry issued findings that blamed unscrupulous manufacturers, a cost-cutting local government, and reckless deregulation for the disaster.

It is unfathomably sad to think of how where the word “promising” once sat in headlines about Khadija, there is now the word “victim.” It is also not an uncommon substitution. It is possible that it– promise replaced with tragedy– is so common that we never really reckon with the magnitude of what we all lose on a daily basis, what words we could have read, what images we could have seen, what ideas we could have engaged but for all the lives that are lost in the quiet by way of apathy. Often, we lull ourselves into the quiet resignation that tragedy is happening over there. Some even find comfort in the idea that those who are dismissed or disregarded are not them, that a misfortune that snuffs out “promise” or the absence of opportunity to cultivate promise will not affect them. But we all lose. We are all losing. Khadija’s images take on a second skin as evidence of this. Had Khadija’s brilliance not been so bright, the utter magnitude of what we have lost in losing her may have been consumed by the quiet as well. Khadija Saye’s life and death is a hard and concrete example of what it looks like when institutions fail us, when the systems that were built to benefit some of us and dismiss others function to rob us all of the full potential of our communities.

But there is light here too, light in knowing that even for those of us who never met Khadija, never were given the chance to stumble upon a larger body of her work at a gallery opening, an art fair, or hung along the walls of our favorite museum, because Khadija made art, it will last, and we will forever have a little piece of her. There should also be comfort in knowing that even for a brief time, she was able to live out her life as the thing she most desired to be: an artist.

As you continue through these images, is there a newfound uneasiness in knowing that the artist will never escape the designation of “promising”? Are you hollowed by the knowledge of her loss, our loss? If so, contemplate what is required of us to mitigate the loss. Sit for a moment with that thirst for more of Khadija’s work. Then, think of what is required of you in acknowledging and nurturing a world in which we lose less of ourselves and less of each other.

In an interview she gave as a featured artist in the 2017 Diaspora Pavillion, Khadija may have left us all a final directive, saying, “The next chapter for me is to continue to bring up these questions.” Let’s keep questioning, for Khadija.

All images from the series ‘Dwelling: In This Space We Breathe,’ 2017

Wet plate collodion tintype on metal, 250 x 200mm

All images courtesy of the Estate of Khadija Saye © 2017

In memory: Khadija Saye Arts at IntoUniversity