“Yes, Chef” Victor Blanchet Always Knew He Would Be Here

The 25-year-old culinary phenomn taking Paris by storm.

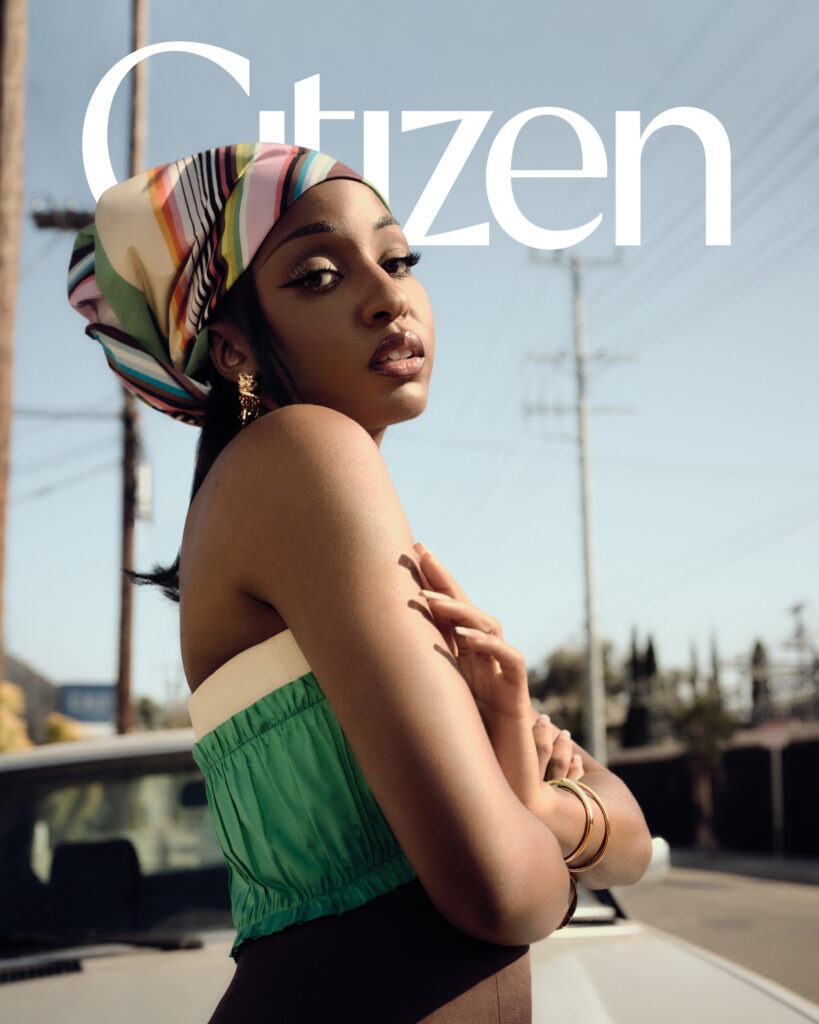

Text and Interview by Kevin Quinn

Images courtesy of Victor Blanchet

“At 14 years old, I already knew I wanted to be a chef[,]that I would open a restaurant and make something important.”

Victor Blanchet looks all about 19 years old. His face is soft, and his dark skin is luminous in the garden where he sits. His presence is eager and accommodating. His enthusiasm and passion for food are apparent in five seconds of talking to him over Zoom. It is late summer in Paris, and Victor has taken time out of his punishing schedule to talk to me. During this brief departure from the pull and strain of the world of Paris haute cuisine, he attempts to offer, in his own words, some sense of why this storied world of rarities and the rarefied—long helmed by chefs of one color and one trenchantly defined style—has rightfully anointed him one of its most deserving (and capable) newcomers.

In fact, Victor is not 19 years old. He is 25. And, despite his charming humility, he is admittedly the phenom he always knew he would be. Though we are conditioned to think of our cultural prodigies as appearing, magically, out of thin air—in existence only at the time that we first notice them—Victor is quick to point out that that is not his story. “At 14 years old, I already knew I wanted to be a chef. When I went to culinary school, I knew that I was going to be more than just a cook. I knew I wanted to be a chef and that I would open a restaurant and make something important,” he tells me.

Born in Haiti, Victor was two years old when he, along with one of his sisters, who was three at the time, were adopted by a French family. He and his sister left Haiti to live with their adoptive parents in Laval, a city in northwestern France. Victor grew up in Laval, about an hour and a half train ride from Paris. When Victor and I first speak, he confidently recalls both a desire to “make it to Paris” and the details of what making it to Paris would look like. In Paris, he would be a chef.

It is mesmerizing to listen to him account for such self-possession, and he lights up even in the timber of his voice as he continues describing the reality of a dream, a goal, or a premonition come true. Now, the Head Chef at Halo, one of Paris’s hottest new restaurants, Victor admits that he now sleeps four or five hours a night.

His is a wonder of an origin story, and even if he always saw himself as a chef, it would have been difficult—in the most hopeful of expectations—to predict that he’d end up where he is now.

Upon finishing culinary school, he worked at a small gastronomic restaurant outside his hometown. It had no Michelin star, he points out, but it trained him well and gave him a necessary induction into the world of food on the level at which he knew he wanted to perfect it. He became heady with inspiration and motivation while there, and after one year, he knew that it was time to leave so that he could move on. And moving on meant working in a Michelin-starred restaurant in Paris so that he could know whether or not the designs he had for himself and his future actually matched his culinary mettle.

“I knew what was going to happen once I started working at a Michelin-starred restaurant. I knew I was going to have to give up my life in a way.”

At this point, as I listen eagerly for the name of the restaurant he had his sights on joining (the foodie in me wants to confirm whether I’ve been to it), he pauses with the reflectiveness of a person who has lived many more years than he actually has.

“I knew what was going to happen once I started working at a Michelin-starred restaurant. I knew I was going to have to give up my life in a way. I knew I wasn’t going to have any free time or that I wouldn’t be able to see my family a lot or have a girlfriend or anything like that.”

He’s talking to me, yes, but I can see that he’s actually talking to himself—taking account, as it were, of the choices he’s made that have gotten him to this point in his career. He wakes up at 6 am, for example, arrives at Halo at 8 am, and doesn’t leave until midnight or 1 am the next day. Then he gets up five hours later to do the whole thing over again. No life? I think that’s understating the matter. And I think he does, too. In fact, no chef at his level would find any of what he describes as his “life” now surprising. The diner in me is grateful for his sacrifice, but does he feel like he’s missing out on some of his youth?

He thought he was initially, which is why he took a trip to the US for three months before moving to Paris for his first serious job at a restaurant. In Hawaii, LA, Miami, and New York, he let himself have a taste of the world that he knew he would never get to see much of—not unless he was working there. He then returned to Paris with the conviction that “the best chefs in France are in Paris. And most of the best chefs in the world are in Paris. For me, it’s where you become a great chef.”

Looking for a model under whom he could learn, he spent his first year in Paris at the one Michelin-starred Neso, under the guidance of Chef Guillaume Sanchez. To most people, that would have been accomplishment enough at his age, but after one year there, he casually concluded, “Okay. I’ve worked at a Michelin-starred restaurant. Now I have to work at one that’s one of the best in the world.”

That mandate brought him to the three Michelin star Arpège, without a doubt one of the finest restaurants in the world. In Victor’s boldness, he sent a note and CV to the restaurant indicating his desire to work there. A week later, they told him they were interested, and after a test hired him two weeks after that. After only one year there, he became the sous-chef.

14-year-old Victor had always seen his star shining, but now everyone else could see it, too. His Arpège experience got him the attention of a Top Chef producer who asked him if he would like to join the show. He did, he responded enthusiastically.

Unsurprisingly, he won Top Chef.

When he returned to Arpège after his win, he only stayed for three months. “All right,” he thought. “Now I need to do something on my own.”

On his own. At all of 24 years old. It wasn’t a strange idea to him (though he confesses to feeling like he might not have been ready), nor was it strange to the business partners who then approached him after seeing him on Top Chef. They wanted to open a new restaurant, and they wanted Victor at the helm.

“It’s hard to be a Black chef. Not just in Paris. Anywhere.”

Sometimes, worlds apart, different people are living out the same inevitability. In these moment, singular lives seem to reflect larger trends, and we come to see just how connected all of our stories are, or just how connected the communities that would otherwise be described as “worlds apart” are. Over Zoom, I ask Victor if he knows who Charlie Mitchell is, he shakes his head no. “He’s the first Black chef to have a Michelin star in New York City,” I say. “Clover Hill in Brooklyn.” There is a silence between us at this point as he thinks what I don’t have to say: why has it taken so long for this to happen—especially in a city like New York? The answer is related, somehow, to what it’s like to be a Black chef—even of Victor’s prominence—in Paris. Or anywhere, for that matter.

“It’s hard to be a Black chef. Not just in Paris. Anywhere. I remember when I was starting out and I arrived at the restaurant. People immediately thought I was there to do the dishes. And when I told them I was there to cook, they looked at me with surprise. It’s hard. And not just if you’re Black. Really, it’s hard if you’re not white.”

And then a familiar distillation: “You have to do more,” he explains, “when you’re Black. You have to prove yourself more. You can have the same talent as a white person but you have to prove that it’s double.” And the cold conclusion: “That’s why Black people don’t stay in restaurants. Even if you have the talent, they will make you wait to get the job you deserve. And you end up wasting time and can’t really get where you want to go in your career.”

It seems as though, even at the beginning, Victor was contemplating this particular phenomenon. “But, I also knew that I wanted to do something important for my community. For Black people. [At 14,] I didn’t have a model of a Black chef in France, but I think it’s very important to have inspiration for your career. It’s very important to have a model.”

Who at 14 thinks of himself as a model, or at least as having the potential to become one, knowing that he’d have to pave his own way to get there?

When I probe a bit more, Victor is happy to point out how things are changing, mentioning Mory Sacko, the Malian, French-born chef and owner of Paris’ Michelin-starred MoSuke restaurant. “He’s the only one, though,” Victor says, floating into a story about a visitor to Halo earlier that month, a Black chef who expressed wanting to work at Halo because “we only have you and Mory Sacko.” During that interaction, Victor notes that he suddenly saw clearly how he might have become that sort of influence he had imagined himself becoming when he first set his eyes on becoming a chef.

Then there is that weird discord between having achieved something and having everyday experiences that seem to dismiss that achievement altogether. It is not uncommon for customers to visit Halo and boldly express a righteous disbelief that Victor is the chef. Partons rarely share the details of their disbelief, but Victor, based on a long history of moving through these spaces, concludes that it is the specific combination of his Blackness and his age that perplexes most. “But did you like the food?” Victor laughs. Indeed, that is the only question that matters.

“I start with the jus.”

The question of most importance for Victor is what kind of jus he’s going to make every day.

If you have to source the internet to figure out exactly what Victor is talking about, it is likely that you are not alone. Michelin’s own website notes that “jus” is “kitchen language” before explaining, “It is a specific type of sauce, made from meat juice that has typically been derived from a roast. It’s thus typically served as an accompaniment to meat, especially roast beef, which is then known as beef “au jus.”

Victor tells me, “I start with the jus. In French culture, the most important thing is the jus. I create a new one every day. But I know you can’t create something good every time you try. Sometimes I make something, and I think, ‘Oh, my God. That’s disgusting. So I try again.”

I think about this when I’m off of the computer and in person at Halo a month after speaking with Victor. I am giddy to have gotten a table (at which I eat marvelously cooked sea bass in a jus that is out of this world). Victor is much taller than I expect him to be. He seems glad to see me but also intensely focused, with only time for a quick wave in the direction of my table while he plates dishes and sends them out to the diners.

After dinner, my friend who has come with me, says it’s one of the best meals he’s had in Paris. He insists on taking a photo with Victor, and he obliges, calmer now that it’s nearing the end of the night.

On his face, I can see the exhale of someone who has completed a job to perfection—someone who knows he belongs in the space to which he has ascended. It’s also the face of someone whose eyes can see a future that not even this elegant restaurant can contain.

Despite all the noise that those suspicious of his place in the Paris food world might lunge his way, Victor seems committed to continuing to try. On our Zoom call, he shares that he eventually hopes that that single-minded, unflappable focus will lead to a second restaurant in Paris and then across the Atlantic in the US. That is his dream.

“The Victor Blanchet brand,” I joke with him.

“Exactly,” he smiles, entirely serious.