An American Inspiration

An American Inspiration

Interview by Danielle Powell Cobb

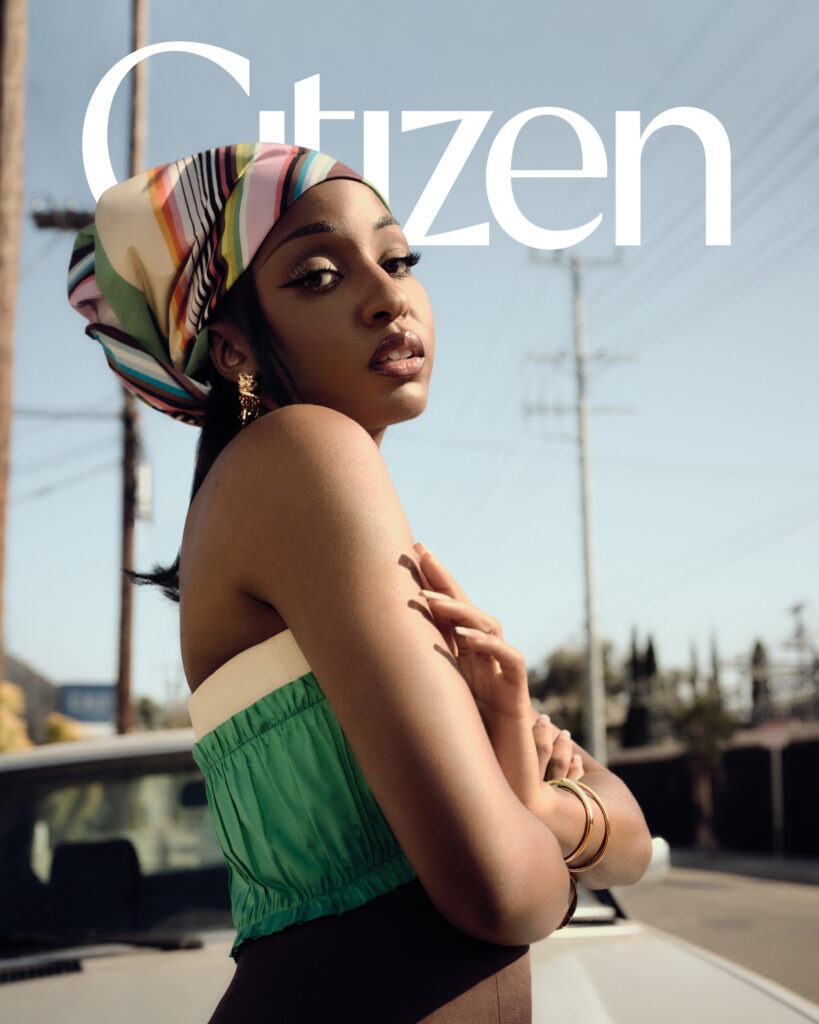

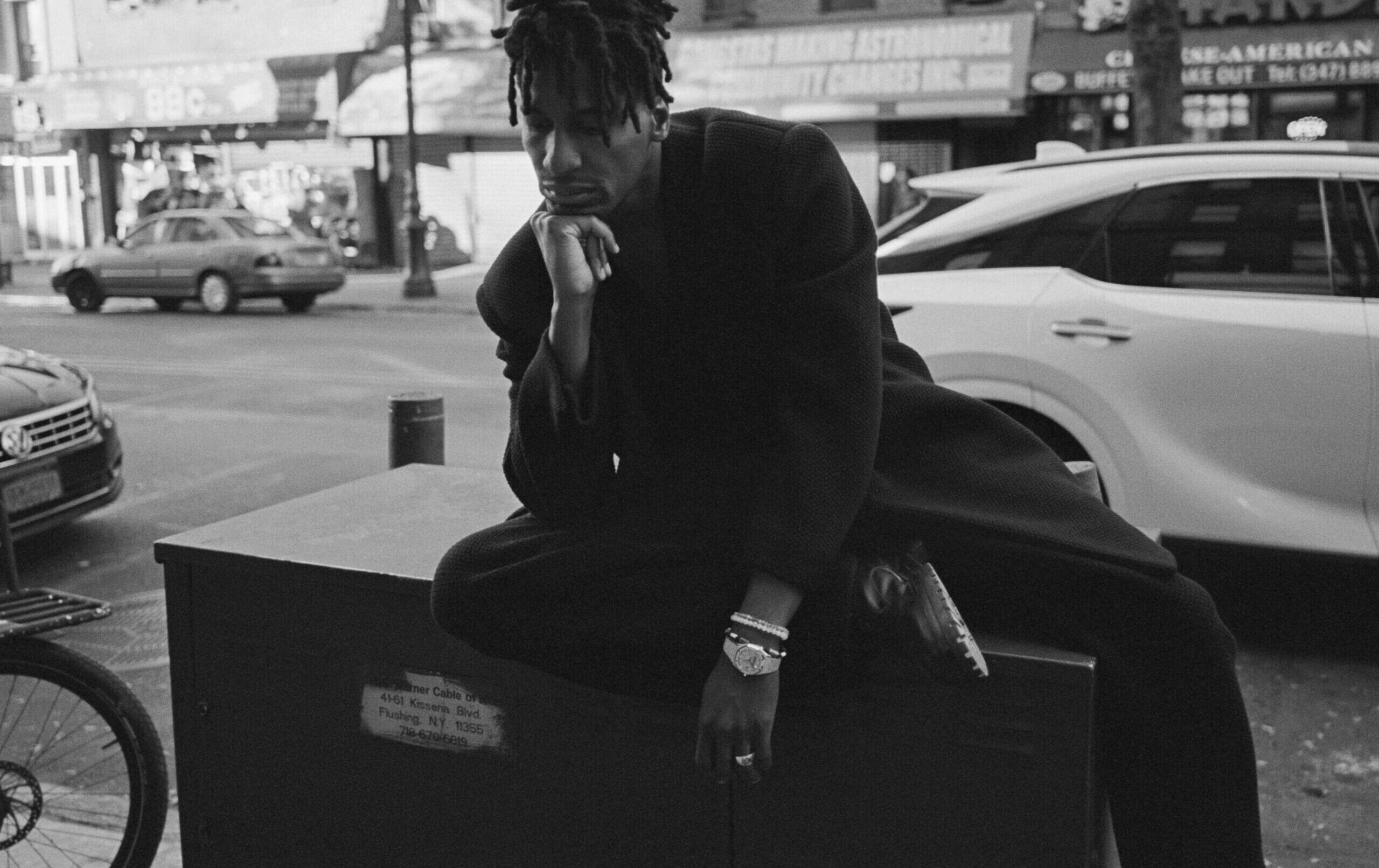

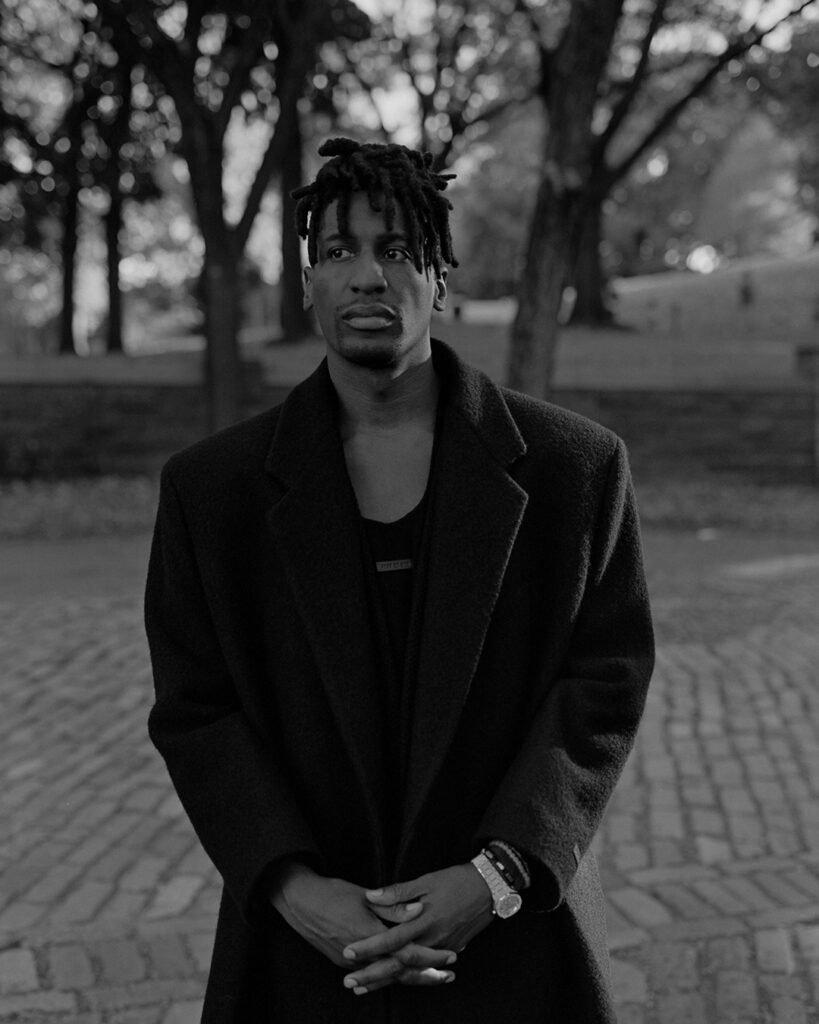

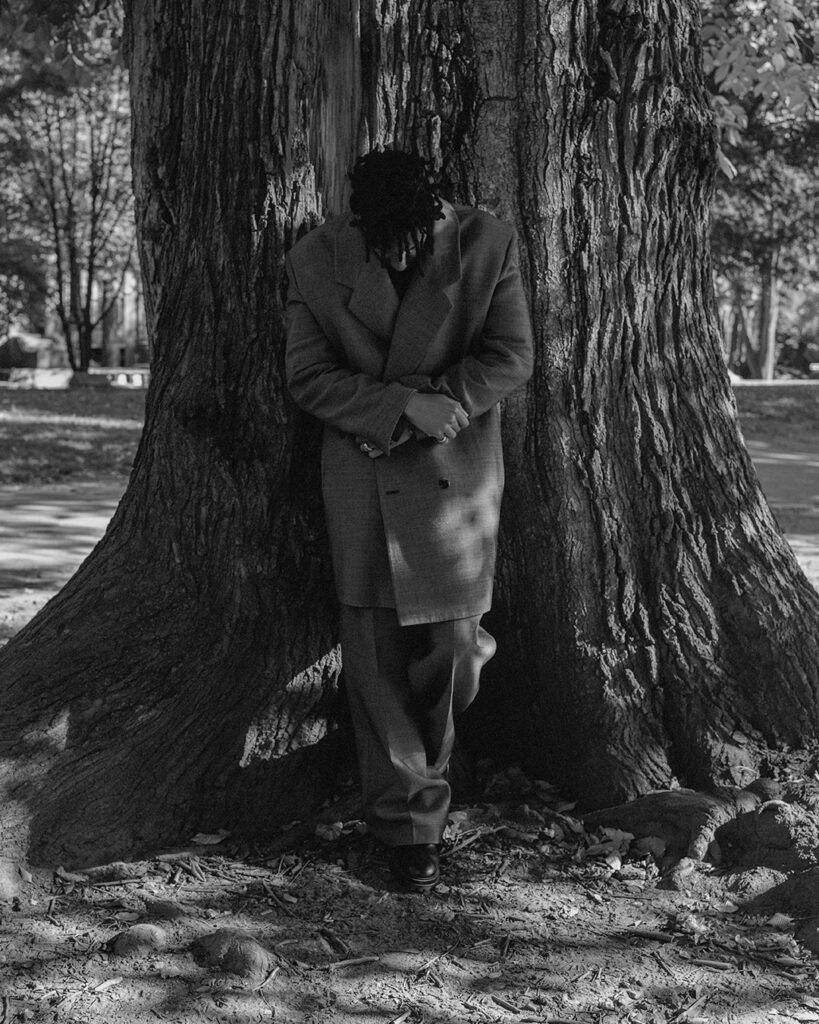

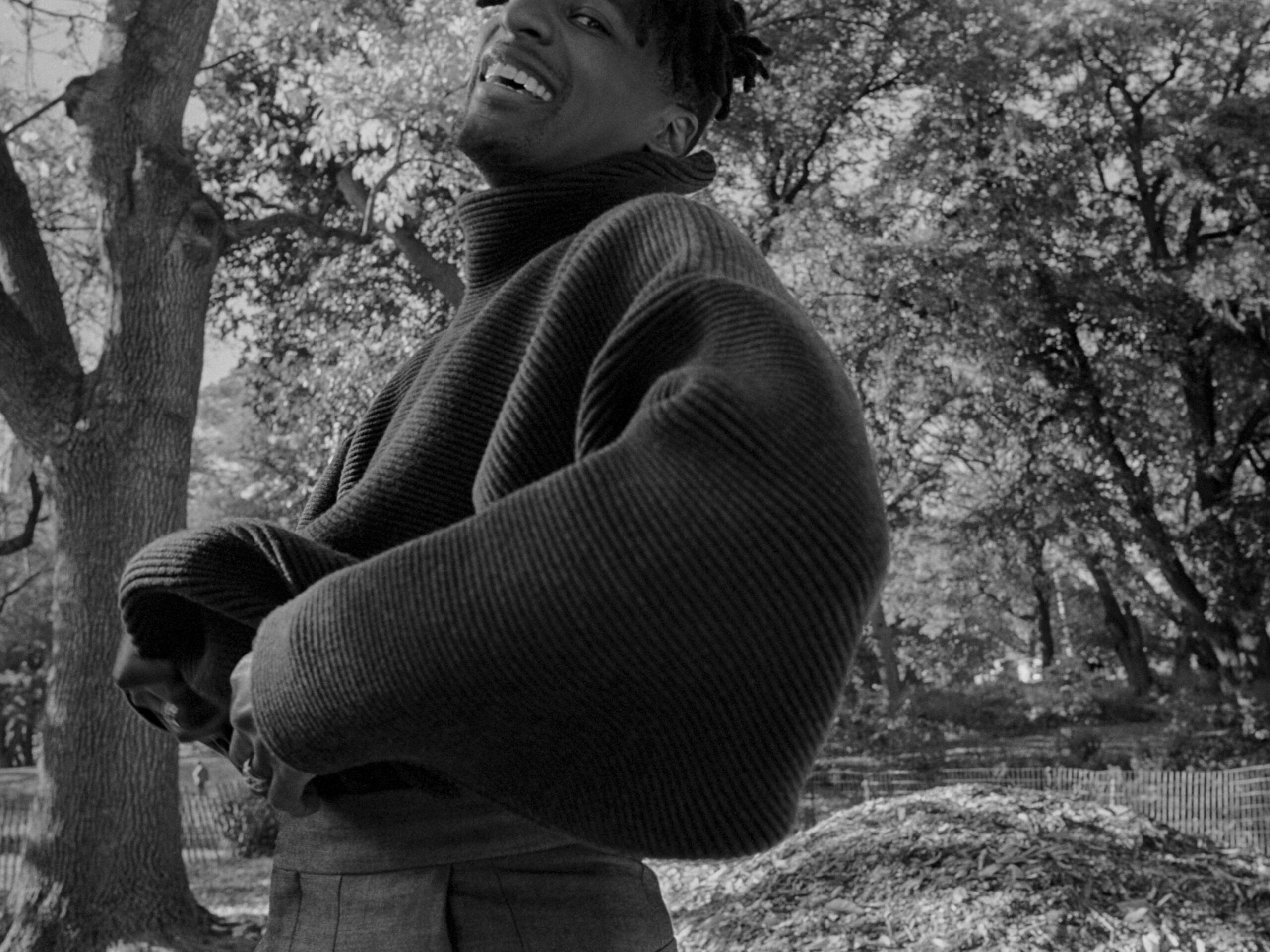

Photography by Andre D. Wagner

Jon Batiste represents all the fairytales deeply rooted within the fairytale of America, a tale of an exceptional protagonist, born from exceptional people, with exceptional talent who overcome exceptional odds, except Jon is not a fictional character, and the story of his life over the last decade need not be embellished or added on to. Jon is big, and bold and bright, few would argue against the idea that he is one of the most gifted musicians of our time, he was born into the Batiste family, a New Orleans musical dynasty that includes Lionel Batiste of the Treme Brass Band, Milton Batiste of the Olympia Brass Band, and Russell Batiste Jr., and in a short time, Jon has transformed from Juilliard student searching for his place in the music industry to winning a Grammy for Album of the Year, winning two Oscars, and becoming the sort of star that could both be familiar to American children watching Sesame Street and perform to an awe-filled crowd at Montreux Jazz Festival in Switzerland.

Jon is the purest representation of an inspirational American character, not because he plays the role prescribed to him but precisely because he does not. He is a Black man from New Orleans who consistently presents as joyful, as hopeful, and humble while carrying the kind of talent that should come with the ego of a villain or at least the reasonable guardedness that so many very famous people carry.

When I first meet, Jon we are outside near his home in Brooklyn. A team of people surround him as the photographer, Andre D. Wagner, readies himself to take his first shots of Jon. Jon is wearing an oversized grey Fear of God coat. Its shoulders cut far beyond his, yet the coat does not swallow him. It is perfect. It almost seems to make him appear to be more of himself, as though a man with such talent and light should only wear clothes that make him seem larger than his human form.

Before Andre gets to work, Jon and I exchange greetings. I offer a, “Hi, nice to meet you,” and Jon offers his signature bright and excited, “Yeah!” and an outward stretched hand. There, Jon sets the tone for a comfortability forged through the kinds of “yeahs” and “okays” that I usually only share with friends. This language of little needing to be said for us to understand each other seems to be the norm for Jon. He assumes familiarity or at least offers it easily to all of those that I see him interacting with on set.

After the shoot wraps, I do not speak to Jon again until we are on a call two weeks later. Then, he is quieter but not quiet. I can hear in his voice that he is tired, but he moves through questions and topics as though he could riff for hours or days. Again, there is that comfortability intertwining with a bigness, an endlessness. It is that endless that is also present in his latest work, “Beethoven Blues,” his first-ever album of solo piano work in which Jon reimagines “the transcendent works of Ludwig van Beethoven alongside original compositions.” This work is indeed confined to 50 minutes and 57 seconds, but through moments of interpreting and adding to music that we are so deeply familiar with, Jon creates the story of an endlessness of possibilities, endless combinations of notes that can make a work or an age-old story something new. And somehow, that seems to be precisely the message–one with no words– that we each need at this very moment.

“Let it wash over you like a meditation or a prayer.”

What follows is our conversation, a brief encounter with someone who at once seems like an endlessly talented genius and familiar friend:

Danielle Powell Cobb (DPC): I only have you for a little bit, so I just kind of wanted to get into it. Number one, I just finished listening to the album. It’s absolutely gorgeous and beautiful and wonderful.

Jon Batiste (JB): Thank you.

DPC: It feels so mystically timely. We did a cover story with André 3000 last year when he released his instrumental album, and the timing of this new album, “Beethoven’s Blues,” reminds me–not stylistically but emotionally–of the experience of listening to André’s album and his insistence that “the world is too loud.” Instrumental music has this way of pushing us inward and quieting the world around us, and man, do we need that right now? What was your thinking behind putting out an instrumental album following the huge success of “We Are”? Why take your voice out of the music when that is what garnered all these accolades?

JB: I think instrumental music carries messages and sounds, and sounds carry meaning. You don’t have to have words for a song to have meaning. In fact, a lot of times, without the words, the meaning is deeper because it hasn’t been simplified or dictated. So, I find that instrumental music is another thing. Who would’ve thought that an artist that’s not just in the space of classical music or jazz, but that inhabits a contemporary space in the culture and is a part of the conversation could make an instrumental music album? This is what I love about André’s thing and about just the idea of artists who are in our position making instrumental music because it then reaches such a different audience that maybe wouldn’t think to pick up a Beethoven record or to pick up an instrumental album that has tracks that are longer than three minutes and to sit with that. And I think that that could change so much of how people feel and think about music and what place it has in their lives. It is such a deep thing. It can be passive, where it’s a part of your daily soundtrack or something that you’re living with. Or [instrumental music] can also be something you put on, and you let it wash over you like a meditation or a prayer.

DPC: There is a great amount of narrative in your music–storytelling. Something that stuck with me when I was watching “American Symphony” was when you said, “Music is inevitable.” I interpreted it to mean all creativity is unfolding, but now that I have you here, I get to ask, when you say music is inevitable, what exactly do you mean?

JB: When music is made in a way that’s coming from a pure intention, and it’s not forced in any way, it’s something that comes from the divine stream of consciousness that all of the creativity in the world comes from, which is inevitable and is always present in the air, is always available to us to be in collaboration with the creator, the greatest creative presence of the universe. In this way, music becomes inevitable because it’s the only possible sound that could happen. It’s the only possible outcome. It’s just the thing that we all in that space would do. It’s like how some of the great songwriters or lyricists, or composers say that the song is already written, the piece is already written, and the theme is already there. I’m just the one who happened to be around to receive it, or I was the one chosen to receive it.

It’s the thing that happens at certain points in the day. Quincy Jones, he would always tell me he loved to wake up at 4:00 AM or stay up until 4:00 AM when he was creating or in the studio because that was the time when the energies were the most present, and he would always talk about wanting to have the ability to create and discover at the same time. He said, “You got to leave. You can’t have your ego taken up the space where God would be in the room.” He was like, at 4:00 AM there’s the presence of the spirit of what we’re trying to do. The world is asleep and there’s a stillness, and what we’re actually trying to do emerges.

DPC: Is that how you work? What time of day do you find yourself working, and how does the work lead you?

JB: I find myself in a deep flow–this is what was similar between Quincy and I– at like 4:00 AM. I like to start after my day has sprung into motion and I’ve had a chance to live a lot of it, and it starts to settle into me, and my subconscious thoughts are full of stimulus from the day. Around four o’clock, five o’clock, just before dinner, I go in [to the studio], and I take some time to get the space ready and in a posture to receive divine creativity. So I get the lighting and the energy and the space right. Then you maybe try some things, then go to dinner. You come back, and it’s about 10 o’clock. Then you’re starting to work, and then you start to really hit a stride after midnight, I usually end up going until about 6:00 AM. That’s kind of the sweet spot from midnight to six, but I start at 4:00 PM.

DPC: I want to step back. I realized I didn’t do something I normally do, which is to say, how are you, Jon?

JB: Ha. Great, great. I just had a birthday, and I spent my birthday doing what we just talked about. Actually, funny enough, I left the studio at 8:00 AM, creating with about 20 or so of my closest friends and collaborators.

DPC: Wait, your birthday was yesterday? Happy Birthday!

JB: Thank you!

DPC: Sounds like you had a joyous one. I think a lot of us are thinking about “joy” and how we sustain our joy even when the world around us feels quite chaotic. What centers you when the world is so noisy?

“Being lost in the creative process and making something out of your anxiety is a centering practice.”

JB: Being lost in the creative process and making something out of your anxiety is a centering practice. It’s something that my wife Suleika calls the “alchemy of creativity”, and I really believe that transmuting something that is heavy and dark into light and creativity is a gift that God has given us to be in the world and allow for us to use our pain to get closer to him and to connect to each other.

DPC: Speaking of connecting, outside of music, what are the other things that inspire your work and your purpose? Is there a writer that comes to mind that you can think of at an early age? Is there an artist? Is there a photographer that you can think of who informed your work in a very substantive way or helped to form the foundation for your work?

JB: I mean, there’s not one, but oftentimes when I think about music, I’m not thinking about music. My influences are the things of life and other mediums of art, but mostly outside of the realm of other songs or composers. There’s something about music in that it influences me, and it connects me to what I’m hearing in a way that makes me want to create that thing. If I’m listening to Frankie Beverly and Maze or if I’m listening to Nina Simone, I’ll want to make something like that, but that’s not helpful in the creative process. I like looking at paintings, and I like reading articles or books or interviews of creatives more so than I actually like to hear music. I am inspired by the things of life, like the feeling of being at a really amazing wedding or what it felt like to play at my grandfather’s funeral. My grandfather was like a Jon Batiste blueprint. If you knew him, then you’d get a lot about where I come from. He passed away recently.

DPC: When did he pass away?

JB: He passed away earlier this year, and we played a tribute to him because he was an elder in the A.M.E. church and a hero in the community.

DPC: Tell me a bit more about him.

JB: He was in the first wave of Black men that integrated the Navy, and he fought in the Korean War when he was 17 years old. He was the postal workers’ union president and the hotel workers union president during the sixties. He was somebody who grew up in New Orleans and had such an incredible arc to his life. By the time he was in the last years of his life, he was at the Grammy’s watching me win and going to the White House and all these things that we did together. He was a man of deep faith and a strong-willed individual. Up until he was in his early nineties, he would run eight miles a day. He ran marathons. He raised eight children with my grandmother Nann–that was her nickname, Nann. My mother is the eldest daughter of eight, and they grew up in the 17th ward in Hollygrove in a house that I would spend so much time in on Hamilton Street in New Orleans. He had this big Everlast punching bag in the back of the house, and every time I would visit him, he would show me how to hit the bag, and we would talk about his life, the sixties, about all of the work he did for workers, about marching with Dr. King and the sanitation workers and, his life of activism.

We recorded him, sort of giving a sermon on my album “We Are,” and used the choir, the Gospel Soul Children, which is the choir from his church. He was sitting in the audience doing the premiere of American Symphony at Carnegie Hall. This all happened in the last five years of his life through his grandson and through my connection to his work, his life, and his lineage.

“[Using] the essence of a moment or a feeling or a thing, and then making it into a musical expression is my thing.”

So when we played for him at his funeral, that feeling–I always think about that sometimes if I’m creating music now, I always reference the feeling that was in the room because it’s just indescribable. But that’s something that is an example of, it’s not music, but it’s an essence of a moment or a feeling or a thing, and then making it into a musical expression is my thing.

DPC: That’s really beautiful. I can only imagine how important that was for him and how moving that was for him to see his life and his lineage almost unfold into something that he probably didn’t even imagine.

I was just kind of looking through and trying to figure out what I want to talk with you about, and I ran across this quote by this writer and physician, Ed Deb Bono. He says, “There is no doubt that creativity is the most important human source of all. Without creativity, there could be no progress and we would be forever repeating the same patterns. When I hear that, I think about the way that creativity kind of pushes us forward as a people, as a society, and wanted to ask you what ways you have sought to break patterns within your own creative field and for what purposes.

JB: Ooh, I think there’s a lot of the same idea being replicated and reproduced in different packages, and I think it’s for many reasons, but the main reason is fear. Fear of change, fear of failure, and I think that we also are in a time where it is hard for us to see how to bring the past into the present to create the future, not to take the past and to try to reenact it but to actually take it into the present and create the future–

DPC: Allow it to inform us?

JB: Right. Exactly.

“Discovery is greater than invention.”

DPC: Do you ever have a fear of people expecting the same from you? With the amount of success you’ve seen over the last few years, do you find it harder or easier to experiment with new ideas, with new sounds, with new projects?

JB: I like being in the beginner’s mind space and not knowing exactly what I’m doing until it reveals itself. I think that that’s the best possible way to embrace new ideas is just to allow yourself to be in a constant beginner’s mind, a constant state of not knowing exactly where you are going or where you’re going to land, but using your intuition and using whatever’s pulling you forward. Discovery is greater than invention. You could think, I want to make something, and you go and you build that thing, or you can say, I feel something; let me go and put myself in a position to discover what that is, and then it reveals itself to you. The same result in terms of something is invented, something new that you form out of the air happens to become a reality, but the way it is happened upon is completely different, and I think it’s more pure and more true and more original than what you could think of and solidified upfront.

DPC: This morning, listening to your album, I was thinking there’s so much familiarity here, not just from the reinterpretation of classical works but then also the jazz influences, the blues influences, the gospel influences; it feels very much like a continuation or another iteration within an American Symphony series, where you’re kind of weaving together all these different genres. Why did you choose to lead with Beethoven’s work? Why did you choose to recontextualize that particular work within this “series”–I’m just going to call it that.

JB: Beethoven is a representation of so much, so much that is positive and so much that we are trying to overcome in terms of the class and culture wars. But, I wonder if Beethoven was here today and his music is so ubiquitous 256 years later, if he had heard blues and gospel and soul and jazz and all of the contemporary innovations of music, would he have incorporated that into his style? Furthermore, would he have this sort of reverent adherence to the sheet music, to never change the notes that you played every performance, or would he be influenced by the work of others who are in his echelon of greatness like Duke Ellington and what he then incorporates that? I think for sure he would.

But then I also questioned if, even when he created the work, he was not improvising. There are incredible accounts of him improvising, and there’s a tradition of spontaneous composition in classical music before black Americans, at the turn of the century, codified the terminology of the blues and the form and the structure of jazz. These different forms of music and all the stuff that came from the communities in our time, these emotions and these feelings existed since the beginning of time. They just didn’t have names to ’em. So it’s all in Beethoven’s music. I felt like, in short, it’s been 250-plus years, and it was due for an update.

“Why do we value one thing as high art over the other?”

DPC: I’ve heard the pretty much debunked theory that Beethoven was Black. And, it seems like we–as in Black people– tend to do that, attempt to connect ourselves through lineage to the things that have been deemed “classical” or rarefied. I wonder if you have any opinion as to what’s going on there? What do you think people are getting at, or what do you think people are trying to say?

JB: Well, it’s not really about race more than it’s about class. What we value is often defined by who sets the template. Oftentimes, the things that are European are considered high class and high-end, and things that come from other communities, other indigenous communities, and other traditions of music aren’t viewed in the same way. So it’s just a question to ask: well, why do we value one thing as high art over the other? Is it inherently that way, or is it just a choice that we’ve made that this thing is to be valued and considered high class, and this other thing, it can’t be that. When they were making it, they weren’t thinking about it as classical music. It didn’t have a name. That was what we put on it after the fact. It wasn’t Beethoven saying, I’m going to write a classical music composition today.

But, the values surrounding our canon are defined by cultural norms and cultural expression and cultural values that a lot of times other people defined and we don’t always agree with. So it’s just the natural cultural reckoning that happens. But, it’s worth fighting for and over.

DPC: Why?

JB: I think everything that we do that’s great, transcends race and transcends boundaries of class and gender. It ties us all into the human family, and that’s the stuff that oftentimes is under scrutiny, so it is worth fighting for because it is actually, ultimately, the thing that will bring us together.

DPC: I’m going to end with a question we always end with, which is, who should I be listening to, and what should I be reading?

JB: Wow. There’s a lot there. I mean, what are you trying to achieve? That’s my follow-up question because I’m often in a rabbit hole based on what area of my life I’m trying to evolve in and align. It’s like you’re cleaning up your algorithm of life to align with those things. Based on the input that you put into the algorithm, you get the result.

Hanif Abdurraqib, do you know him? He’s an author.

DPC: I do. I’m actually a huge fan of his work!

JB: Oh, great. Yes, yes.

DPC: Okay, so I’m reading more Hanif. Great, and gladly! And what should I be listening to other than your album, of course?

JB: Yeah. There’s a trumpet player named Giveton Gelin. He’s from the Bahamas, and he has his own unique sound that blends Bahamian music–his father’s a pastor, so he blends gospel and he also blends jazz. He is also a mentee of the late Roy Hargrove. So he has the sound of Roy in his playing, blended with his own sound. He’s the next one on the trumpet, for sure.

DPC: Okay. I’ll have to check him out. I’m going to let you go, Jon. I know you were up until 8:00 AM, and I made note of that when you said it. Thank you so much for speaking with me. Please get some sleep. Thank you for being you. I can’t wait for the rest of the world to hear your album.

JB: Yes, indeed. We’re rolling.